With a plaque to their memory due to be re-dedicated later this month, DAVID CONNOLLY tells the story of the ILP volunteers in the Spanish Civil War and their connection to POUM.

Until recently the ILP’s contribution to the Spanish Civil War has been given scant recognition on the left. Indeed, for many years it was largely ignored except by those critical of the role played by George Orwell. It’s true that the ILP volunteers were small in number and saw a limited amount of military action but they were part of the international support movement for the Republic and some of them were witnesses to the dramatic events of the May Days in Barcelona in 1937. It is only right that their commitment and sacrifice should be honoured.

After its disastrous decision to disaffiliate from the Labour Party in 1932, the ILP left the mainstream socialist Second International two years later. Being neither Stalinist nor Trotskyite, it joined a group of Marxist and socialist groups in the International Bureau for Revolutionary Socialist Unity, better known as the ‘London Bureau’, the location of its headquarters until 1939.

After its disastrous decision to disaffiliate from the Labour Party in 1932, the ILP left the mainstream socialist Second International two years later. Being neither Stalinist nor Trotskyite, it joined a group of Marxist and socialist groups in the International Bureau for Revolutionary Socialist Unity, better known as the ‘London Bureau’, the location of its headquarters until 1939.

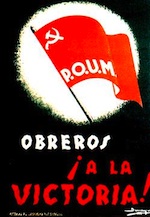

The ILP general secretary, Fenner Brockway, was its chairman and the groups affiliated to it were generally small, dissident parties including: the French Workers and Peasants Socialist Party, the French Party of Proletarian Unity, the German Socialist Workers Party, the German Communist Right, the marvellously named Italian Maximalist Socialists, the Dutch Revolutionary Socialist Workers Party, the Polish Bund, the Romanian Independent Socialist Party and the Norwegian Labour Party, which was the largest with 80,000 members. In Spain the affiliated organisation was the Partido Obrero d’Unificacion Marxista (Workers Party of Marxist Unification), POUM for short.

The ILP was active in support of the Republican cause from the start of the war, raising money to buy medical supplies and equip an ambulance, which was driven to Spain and presented to POUM. In 1937 they borrowed money to send a food ship to Bilbao to feed the starving Basques but this was blocked by the British government acting in the name of ‘non-intervention’.

The ILP sent three delegations to Spain seeking to persuade the Republican government to release POUM prisoners and unsuccessfully tried to organise a prisoner exchange with the rebels to free one of the POUM leaders, Joaquim Maurin, who had been caught behind the lines in Galicia at the start of the hostilities. The ILP arranged accommodation for Basque refugee children in Somerset, courtesy of the Clarks shoe family who were Quakers, and it also took part in joint ‘Spanish Aid’ activities with the Communist Party and the broad left in Britain.

Most important of all, they sent a small contingent of volunteers to Catalonia to fight with the POUM militias, even though this did not meet with universal support within the ILP itself. Pacifist members of the organisation objected to the abandonment of pacifism, Catholics in Glasgow took exception to attacks on the Catholic Church in Spain and others questioned the quasi-revolutionary rhetoric that the Party adopted in supporting POUM. In addition, tensions arose with the Labour Party whose official line was to support ‘non-intervention’, and with the Communist Party who accused the ILP of ‘Trotskyism’.

The proposal to send a contingent to assist the military struggle originated with Bob Edwards, who later became a long-serving Labour MP in the West Midlands, and an article appeared in the New Leader on 4 December 1936 while adverts for recruits were published in subsequent issues.

The first group of 25 volunteers, most of them members of the ILP, left Victoria Station on 8 January 1937 but not without the attention of Scotland Yard detectives who observed the gathering. Two hours later the British government made it illegal to volunteer to fight in a foreign war. It took the volunteers two days to reach Barcelona where they were taken to the Lenin Barracks to begin their training. Few had any military experience.

The key ILP figures in organising the contingent were Brockway, John McNair, who ran the office in Barcelona, and Ted Fletcher, who worked with McNair and later became the MP for Darlington from 1964 to 1983.

On 20 January the group took a slow train to the POUM stronghold of Lerida, where they were fed, before travelling on to Barbastro and then to the Aragon Front at Alcubierre. On each occasion they were sent on their way by a POUM band and cheering crowds. At the front they became part of a POUM militia centuria of 100 soldiers, commanded by the remarkable Georges Kopp, and they took up position on Mount Oscuro near Zaragoza. Within four days, 16 enemy soldiers had deserted to them.

At this stage of the war the militias discussed their military decisions in a highly democratic manner involving both officers and men, all of whom received the same pay. In mid-February they moved to another part of the front, close to Huesca, and it was here that Orwell took over as leader of the ILP group. They were shelled each lunchtime, bombed by the Italians and participated in an operation that pushed the frontline forward by more than half a mile.

On 13 April, 15 ILPers took part in the night attack at Ermita Salas, which is described in detail by Orwell in Homage to Catalonia. In the book he also describes life in the trenches, the lice and the rats, the intense cold at night, the terrible food and the boredom suffered by men who were poorly trained and badly clothed, using weapons that were often decades old. But despite all of this they performed well under fire, and morale and discipline were good – the volunteers were dedicated to the cause.

POUM

The POUM had been formed in September 1935 through the merger of the second largest left-wing force in Catalonia, the Workers and Peasants Bloc (BOC) led by Joaquim Maurin, which had 7,000 members, and the very small Left Communist Party, led by Andre Nin, which had no more than a dozen members.

BOC controlled a significant number of branches in the Socialist UGT trade union and the anarchist CNT union, strongly favouring an alliance of all left parties, a position rejected by the communists, socialists and anarchists. They had broken away from the Spanish Communist Party in protest at its sectarian hostility towards non-communists. Together, Maurin and Nin wrote POUM’s political programme but when Maurin was captured Nin became its leader.

BOC controlled a significant number of branches in the Socialist UGT trade union and the anarchist CNT union, strongly favouring an alliance of all left parties, a position rejected by the communists, socialists and anarchists. They had broken away from the Spanish Communist Party in protest at its sectarian hostility towards non-communists. Together, Maurin and Nin wrote POUM’s political programme but when Maurin was captured Nin became its leader.

In the election of February 1936 POUM stood as part of the Popular Front and by July its membership had increased to 10,000. It had a youth wing, the Iberian Communist Youth led by Wilebaldo Solano, and several newspapers. The most important, La Batalla, claimed a daily print run of 30,000. It was a small, highly motivated, Marxist, anti-Stalinist party that believed in revolution from below but, according to Solano, ‘always took into account the specific circumstances in which it had to act’.

The military revolt in July 1936 had sparked fighting in all of Spain’s large cities. In Barcelona the people took up arms and the rebels were defeated with the workers and peasants spontaneously taking over many factories and farms. In this way a situation of ‘dual power’ arose in which the power of the Catalan government, and to a lesser extent, the Republican government, now in Valencia, co-existed with that of grassroots revolutionary activism. To bring some degree of co-ordination to this volatile situation, the Committee for the Militias was established, uneasily combining those who wished to develop the revolution and those who wanted to curtail it.

According to one estimate, some 18,000 industrial and commercial enterprises were seized in Spain as a whole, of which 3,000 were in Barcelona and 2,500 in Madrid. The communist railway worker, Narciso Julian was impressed: “It was incredible, the proof in practice of what one knows in theory: the power and strength of the masses when they take to the streets. Suddenly you feel their creative power; you can’t imagine how rapidly the masses are capable of organising themselves. The forms they invent go far beyond anything you’ve dreamt of, read in books.”

But Josep Costa, secretary of the CNT textile workers in Badalona, was surprisingly ambivalent: “The workers were ready to work but there was no management, no orders, no system … why did we decide to forge ahead with the revolution anyway? Because we had no option. We were being pushed by the workers themselves. That is what we had always preached, now we had to put it into practice regardless.”

The historian Paul Preston explains why some were so keen to take direct action, pointing out that “the five years of the Republic (from 1931) had stripped the Spanish working class of any illusion about the capacity for reform of bourgeois democracy”.

For a brief period there was widespread terror directed against supporters of the right wing parties and the clergy. At the same time, however, Franco’s army was advancing against the Republican forces and militias who found it very difficult to co-ordinate their efforts, some having no great desire to do so.

The ultimate political issue was to do with the primacy of revolution or the primacy of war: the Communist Party, the right of the Socialist Party and the bourgeois Republican parties argued that the war must be won first in order to enable social change to take place later. To do this, political power had to be centralised, social order re-established, strict military discipline enforced and a broad alliance of political support, including from the urban middle classes, constructed.

But for the CNT, POUM and the left of the Socialist Party, sustaining the workers and peasants’ revolt against private property, and creating an economic democracy, was itself an essential pre-condition for winning the war against Franco. For them, social upheaval would lead to military victory. As the Italian anarchist, Camilo Berneri, said before his murder in May 1937, “the dilemma war or revolution has no meaning. The only dilemma is this – either victory over Franco through revolutionary war or defeat”.

Barcelona

In the autumn of 1936 the Committee for the Militias was disbanded and normal government began to re-assert itself with POUM accepting an invitation to join the Catalan administration, although as Solano points out, this was, “bitterly disputed within POUM which was not a monolithic party”. Andre Nin became the Minister for Justice doing a fair and highly competent job but, at the insistence of the Communist Party which was rapidly extending its influence, both he and POUM were ejected from the government in December.

By this time POUM’s membership had reached 70,000 but central government policy in Madrid was being shaped by the need for Soviet aid and, as a result, their suppression and that of the CNT became an urgent priority. Tensions rose rapidly in the spring to the point where the May Day parades in Barcelona had to be cancelled for fear of violence.

Events came to a head on 3 May when the police took control of the telephone exchange in Placa Catalunya from the CNT, which led to a general strike and street fighting that lasted for six days. The central government took charge of public order in Catalonia on 6 May when the elite Assault Guards arriving from Valencia to physically assert their authority.

POUM’s leadership did not want to be drawn into a fight which they knew would damage the Republican cause but, once it had started, they felt they had to support the anarchists as well as some of their own members, who had been caught up in the conflict. They knew it was an uneven military struggle which could not be won.

Orwell was present in Barcelona during the May Days and he describes his experiences vividly in Homage To Catalonia. Five hundred people were killed, 1500 wounded and 200 arrested.

Communist propaganda condemned POUM as both ‘Fascist’ and ‘Trotskyite’ but for a few weeks after the fighting had ended nothing much happened. Then on 16 June the suppression began when Nin and the POUM executive were taken into custody, and 1,000 members imprisoned, of whom 50 were murdered. Nin himself was tortured by agents of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, and when he refused to confess his ‘crimes’ he was killed in a brutal manner.

POUM was now made illegal and in October 1938 its leaders were put on trial although, to the credit of the Spanish judiciary, they were cleared of the most serious charges of espionage and treason. They were, however, found guilty of rebelling against the Spanish government.

The future Social Democratic Chancellor of West Germany, Willy Brandt, was in Catalonia at the time, briefly meeting Orwell, and he sums up the situation: “The POUM in partial agreement with the Anarcho-syndicalists … supported the view that the revolution was the overriding concern. The Communists, in partial agreement with the ‘bourgeois’ Democrats, took the opposing view that the demands of the war took precedence. In trying to arrive at a view of my own I fell out with the revolutionaries, who seemed to me to have overshot the target by a wide margin, but I disagreed even more violently with those who sought to exploit the discipline which the military situation demanded by establishing a system of one-party rule.”

Assessment

POUM were great optimists who believed that the time had come for massive change and in this they reflected the feelings of many ordinary workers and peasants. They thought what had been achieved in Catalonia could also be achieved in the rest of Spain, and they were impatient to get on with it – Solano says that in retrospect they were too optimistic and too impatient.

The defeat of the CNT in Barcelona and the subsequent suppression of POUM enabled the Communists to impose discipline on the Republican military forces, bringing the revolutionary phase of the war to an end. Remarkably, some POUM fighters, including Georges Kopp escaped to France and fought with the resistance against the German occupation in the Second World War.

After the death of Franco, POUM participated in the 1977 elections in Spain but their last surviving branch closed in Valencia in 1981. The Andre Nin Foundation keeps the memory of POUM alive in Spain today.

The author Chris Hall says that between 40 and 45 people went to Spain with the ILP and his book, ‘Not just Orwell’, provides a fascinating portrait of many of the volunteers, including two women, Sybil Wingate and Eileen O’Shaughnessy.

Most ILP volunteers were forced to flee Spain when POUM was outlawed, including Bob Smillie, the 22-year-old chair of the ILP’s Guild of Youth, who was arrested by police at the French frontier. Imprisoned in Valencia, he fell ill and died tragically of peritonitis on 11 June. Orwell described him as the best of the ILP volunteers, a “brave and gifted boy, who had thrown up his career at Glasgow University in order to come and fight against fascism and who, as I saw for myself, had done his job at the Front with faultless courage and willingness”.

In the overall scale of such a huge and complex conflict the military significance of a relatively small number of courageous comrades is necessarily limited. They were just one of the many strands of international solidarity for the Republican cause. But their story is one of the most remarkable and honourable chapters in the history of the ILP.

—

A plaque commemorating the ILP volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, housed in the Working Class Movement Library in Salford, will be re-dedicated on 24 September by the ILP, The Orwell Society and others. Click here for more information.

This article is based on a talk given to the Durham WEA Study Group ‘Politicians, Thinkers and Activists’ in February 2016 using information from Chris Hall’s excellent book ‘Not just Orwell’ as well as several other sources.

Further reading:

Fenner Brockway, Inside the Left, Spokesman

Bernard Crick, George Orwell: A Life, Penguin

Christopher Hall, ‘Not just Orwell’, Warren & Pell

George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia, Penguin

Andre Nin Foundation

Peter Preston, A Concise History of the Spanish Civil War, Fontana Press

Wilebaldo Solano, ‘The Historical Significance of the POUM’.

Barry Winter, Land and Freedom, ILP (available for £4 here)

Ken Loach’s compelling film, Land and Freedom, captures the spirit of the Catalonian revolution at the time.

12 September 2016

That’s a fair point about the John McNair pamphlet Graham.

9 September 2016

David Connolly, the author of this piece, has woven together a very good account in a few short paragraphs of the military story of the demise of the Spanish republic in the 1930s.

I sometimes ask myself if I would have been brave or foolhardy enough to have attempted to join the ILP contingent to fight in Spain back then.

I do think that there is an interesting parallel in today’s world.

The ILP contingent faced real barriers in getting to Spain. The tone of David’s article is that we applaud those men (I think they were all men).

Nobody would support the ISIS-inspired attacks on civilians in European centres. But what is the justification for stopping men and women who feel inspired (and I think wrongly!) by the ISIS cause for travelling to Syria and Iraq to discover their own Spanish republic ‘revelation’?

In conclusion, I would ask why Further Reading didn’t include the ILP pamphlet Spanish Diary by John McNair.

The shattered optimism of what McNair thought the ILP could do in Spain was expressed in the tired, relieved and grateful closing sentence of the diary as he escaped Spain – “We were in France.”