MATT PERRY marks the 85th anniversary of the Jarrow Crusade with a call for the revival of the grassroots campaigning politics that roused the marchers on their month-long trek and helped Labour recover from electoral disaster in the 1930s. It was, he says, ‘a plea against British society’s inequalities and injustices’.

Between 5 October and 1 November 1936, 200 jobless men marched from Jarrow to London in the hope that public sympathy would make the government act on their behalf and force the Bank of England to release funds for a steelworks to save their town. The Jarrow Crusade, as the organisers called it, continues to fire the public imagination.

Anniversaries do funny things to history. They remind us that we are the product of our pasts. Usually it is institutions with resources – the BBC, the main political parties, museums – that set commemorative agendas. This is certainly true of the Jarrow Crusade. Historians can become a small voice at such moments and can be heard, although often at one step removed.

Anniversaries do funny things to history. They remind us that we are the product of our pasts. Usually it is institutions with resources – the BBC, the main political parties, museums – that set commemorative agendas. This is certainly true of the Jarrow Crusade. Historians can become a small voice at such moments and can be heard, although often at one step removed.

At the 80th anniversary of the Jarrow Crusade, I – along with local museums, Crusader descendants, schools and filmmakers – helped organise a commemoration that valued the experiences of those living in Jarrow then and now, and demonstrated the profound connections between the past and present. I hoped to resist pressure to situate the Crusade as part of a conformist national myth of the past.

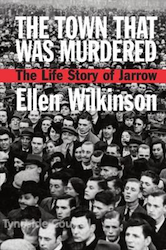

As time moves on, so too does the relevance of the past, so each anniversary shifts the meaning of the Crusade. In my introduction to a new edition of Ellen Wilkinson’s The Town That Was Murdered, the Jarrow MP’s socialist classic about the march , the town’s history and its social conditions during the depression of the 1930s, I outlined the event’s contemporary relevance.

I argued that the story of the Jarrow Crusade could connect three generations’ experiences of unemployment, economic crisis and austerity: the Crusade generation of the 1930s, the Thatcher generation of the 1980s and the present generation, many of them Jeremy Corbyn-supporting millennial. The Grenfell disaster, the bedroom tax, foodbanks were my points of reference, all symptoms of more than a decade of austerity.

In the year and a half since that book’s publication, the situation has changed beyond recognition: Boris Johnson’s premiership, Labour’s electoral devastation in the north of England, Corbyn’s loss of the party leadership and, above all, global capitalism’s farming and development practices that have contrived to produce a worldwide pandemic of a scale not seen since 1918-’19.

Many of these developments echo the themes of the Jarrow Crusade with renewed resonance.

The health divide

The Covid-19 pandemic underlines the importance of health inequalities in the UK, then and now. The route of the Crusade spanned England’s social and health divide, which was more than a simple north-south divide.

On the 80th anniversary, our commemorative project concentrated on inequalities in non-infectious disease, especially those that highlighted a link between unemployment and malnutrition, namely infant and maternal mortality. Wilkinson cited shocking statistics at public meetings along the route, culminating in the demonstration at Hyde Park on 1 November.

For instance, Market Harborough’s infant mortality stood at 33 per 1,000 while Jarrow’s was 104 per 1,000. Red Ellen would not have blushed while pointing out to a Market Harborough audience that a child born in the Leicestershire town was three times more likely to survive to its first year than an infant born to the Jarrow fathers present in the room.

For instance, Market Harborough’s infant mortality stood at 33 per 1,000 while Jarrow’s was 104 per 1,000. Red Ellen would not have blushed while pointing out to a Market Harborough audience that a child born in the Leicestershire town was three times more likely to survive to its first year than an infant born to the Jarrow fathers present in the room.

The incidence of non-infectious disease reflected a constant statistical correlation between poverty and ill-health. Infectious disease was no less connected to social conditions, but the relationship was less predictable. Before the arrival of the NHS, infectious disease was still a major killer. Now, for the first time since the 1930s, it has again become a central public health concern.

At the time of the Jarrow Crusade, tuberculosis, scarlet fever and pneumonia stalked the overcrowded streets of Jarrow. The Labour council – elected in 1935 – was doing what it could to address overcrowding. But, as Jarrow’s Medical Officer of Health reported in 1936: “Unfortunately the Government reduced the subsidy for the erection of houses under the Housing Act 1936, thus increasing the financial burden on local authorities in carrying out their housing programmes, especially where these are incomplete to any large extent.”

Well before the concept of neoliberal moral hazard, the decisions that had transformed Jarrow into a derelict ruin were, for Wilkinson, criminal, resulting in a heavy toll of suffering and death. The governments of Ramsay MacDonald and Stanley Baldwin had responded ideologically with a market-based approach to economic downturn and the public health catastrophe.

Wilkinson highlighted the everyday human consequences of the crisis, asking why children were dying due to malnutrition and mothers went unprotected by national health insurance when their occupation was more dangerous than working in a factory.

Another part of the Jarrow Crusade story is the Labour Party’s electoral recovery from the debacle of 1931 when it lost many of the parliamentary seats that turned blue at the recent 2019 general election. Wilkinson lost her Middlesbrough East seat in 1931 but helped Labour recapture Jarrow in 1935.

In The Town That Was Murdered, Wilkinson outlined how economic orthodoxy and international finance capital had forced Labour prime minister MacDonald in late summer 1931 to impose cuts on the unemployed. That debacle led to the second Labour government’s collapse. At the Palace’s request, MacDonald formed a cross-party national government, splitting the Parliamentary Labour Party in the process. A snap election was called.

Even cursory comparison between Corbyn’s media treatment during the 2019 election and Labour in 1931 is instructive. Wilkinson attributed the 1931 election defeat to the mass psychology of fear. The press, the BBC, the church, employers and social workers had created a “grand wind-up”, she said.

She reported impoverished mothers in Middlesbrough worrying about the fate of the pound if Labour won, and street meetings at which people honestly believed Labour ministers had stolen people’s Post Office savings. Noting that newspaper publisher Lord Beaverbrook had supplied the Conservative slogan, ‘Empire free trade’, that popularised the otherwise dull tariff reform policy, she asked what he expected in return.

The Big Meeting

Labour was able to rebuild after 1931 through mass campaigning. Jarrow illustrated this well. In 1932, Wilkinson became Jarrow’s prospective parliamentary candidate. The constituency overlapped with the Durham coalfield. First invited to speak at the Durham Miners’ Gala in 1927, the year following the general strike and miners’ lockout, Wilkinson regularly attended the event as a County Durham MP.

The Gala continues – despite its interruption due to the pandemic – and Wilkinson’s face features on the remade Follonsby Miners’ Lodge banner, a former pit in her Jarrow constituency.[1] She described the event as a “baptism in trade union solidarity” for the young people in the coalfield.[2] The Gala remains the largest regular event on the UK Labour movement’s calendar and in recent years it had swelled with enthusiasm for Corbyn’s Labour leadership.

The Gala continues – despite its interruption due to the pandemic – and Wilkinson’s face features on the remade Follonsby Miners’ Lodge banner, a former pit in her Jarrow constituency.[1] She described the event as a “baptism in trade union solidarity” for the young people in the coalfield.[2] The Gala remains the largest regular event on the UK Labour movement’s calendar and in recent years it had swelled with enthusiasm for Corbyn’s Labour leadership.

In 2016, during Owen Smith’s leadership challenge, the Durham Miners’ Association assembled MPs who had rallied to the beleaguered Corbyn.[3] The Labour leader addressed the issues facing the movement after the Brexit vote, putting an internationalist case in a region that voted heavily for Brexit, and not dismissing working class Brexit supporters as a homogeneous racist block.

The following year the event took place in the exuberant aftermath of the 2017 election result, when everyone expected the ‘unelectable’ Corbyn’s humiliation, only for Theresa May to lose her overall majority. The crowd chanted “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn” and the greatest cheer went up when he declared New Labour dead.

Demonstrating the resilience of class politics, more than 100,000 continue to attend the ‘Big Meeting’ that first took place in 1871. The Gala’s vitality is symptomatic of the spent fortunes of New Labour and the advocates of the service model of trade unionism, in which cheap credit cards are used to attract new individual members, rather than an approach focused on collective workplace organisation.

In discussing Jarrow’s mining past, Wilkinson sought to distill the lessons of working class history for her contemporary audience. The Gala plays a similar function today. Sometimes wrongly perceived as nostalgic, it has become a model of how to retain a mass platform for socialist politics, working class identity and trade unionism.

In Jarrow, Wilkinson’s response to MacDonald’s “dreadful betrayal” was a protest march from Jarrow to Seaham in January 1934 to lobby the prime minister in his own constituency. Three hundred men and women accompanied Wilkinson on the 15-mile trek. Their placards demanded “steamships not hardships” and “shipyards not graveyards”. Police prevented them assembling directly outside the house where MacDonald was staying but a delegation did get to see him. Having organised it in 10 days, Harry Stoddart, Wilkinson’s election agent and an ILPer, reported that the event “will long remain with us a very happy and treasured memory”.

Campaigning grassroots politics

In the months before the general election, Wilkinson engaged in grassroots mobilisation around the Jarrow constituency. She spoke alongside Will Lawther of the DMA at Jarrow’s May Day event on 4 May 1935, and led the local women’s sections in June at the Durham Women’s Gala before speaking at Wharton Park. When she returned on 10 September 1935, Stoddart had arranged five big meetings in Felling, Wardley, Jarrow and Hebburn with thousands attending.

Given the momentum in Jarrow, Wilkinson’s victory at the 1935 general election was no great surprise, although it was far from a safe Labour seat. Despite facing only the sitting Conservative MP, Wilkinson won with a relatively small majority of 2,350 on 14 November 1935.[4]

Reminiscing about Wilkinson in Jarrow, Arthur Blenkinsop, a post-war north east MP and city councillor, wrote of her influence on him during his youth, drawing him into Labour politics. Until the war, he worked closely with Wilkinson and Stoddart on the anti-means test campaign, Spanish Medical Aid and other anti-Franco meetings. One of the first public meetings he spoke at was against the means test alongside Wilkinson in the streets of Felling.

Reminiscing about Wilkinson in Jarrow, Arthur Blenkinsop, a post-war north east MP and city councillor, wrote of her influence on him during his youth, drawing him into Labour politics. Until the war, he worked closely with Wilkinson and Stoddart on the anti-means test campaign, Spanish Medical Aid and other anti-Franco meetings. One of the first public meetings he spoke at was against the means test alongside Wilkinson in the streets of Felling.

He remembered the time he spent at 5 The Crescent, Gateshead, in discussion with Wilkinson and Stoddart. Stoddart lodged with two other ILP families: the Haigs and the Shepherds. This was where Wilkinson often stayed when she was on Tyneside. Labour recovered from its disaster of 1931, not only in Jarrow but elsewhere too, with a campaigning grassroots politics.

The Jarrow Crusade was a plea against British society’s inequalities and injustices. After a decade and a half of austerity, exacerbated by a global pandemic and three decades of neoliberalism, the geographical, material and health inequalities today parallel those articulated in The Town That Was Murdered.

We have to be honest about the Crusade’s outcome, however. In a letter thanking the pacifist campaigner Dick Sheppard for supporting the march, Wilkinson reflected on the failure of its non-political approach: “I put all my hopes in being super-constitutional. Now the other marchers are saying, ‘See what Ellen got for being good.’”

—-

Matt Perry is a reader in Labour History at Newcastle University.

He is the author of ‘Red Ellen’ Wilkinson: Her Ideas, Movements and World, Manchester University Press (2015), and The Jarrow Crusade: Protest and Legend, University of Sunderland Press (2005), among many other publications.

Notes

[1] The Journal, 14 July 2012.

[2] Tribune, 16 July 1937.

[3] The Chronicle, 12 June 2017.

[4] The Conservatives received 46.9% of the vote. Maureen Callicott, ‘The making of a Labour stronghold: electoral politics in Co. Durham between the two World Wars’, and Ian Hunter, ‘Labour in local government on Tyneside 1883-1921’, in Maureen Callicott and Ray Challinor (eds), Working Class Politics in North East England, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1983, pp.63-78.

AW Purdue, ‘Jarrow politics, 1885-1914: the challenge to Liberal hegemony’, Northern History, 18, (1982), pp.182-198.