GRAHAM TAYLOR traces the birth, growth and continuing struggles of the Quaker left and its ethical ideas.

Quakerism was born in the midst of revolution – the bloody English Revolution of the 17th century. When Quaker founder George Fox was seeking the ‘Truth’ in Mansfield in 1647, Oliver Cromwell had just defeated king and church. Two years before, the Archbishop of Canterbury had been beheaded on Tower Hill. Two years later, the king was beheaded at Whitehall Palace.

In that climate, no wonder Quakers accumulated a store of egalitarian practices aimed at the church and the upper classes: they disrespectfully used ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ to address social superiors; they refused to doff hats to superiors; they refused to swear oaths that superiors were not asked to swear; and they refused to pay tithes to upper-class priests.

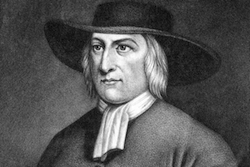

For this defiance Quakers were repeatedly beaten up and imprisoned. Yet Fox (pictured left) went on to demand honest trading, higher wages, lower rents, relief for the beggars on the streets, and an end to the enclosure of the people’s common land.

For this defiance Quakers were repeatedly beaten up and imprisoned. Yet Fox (pictured left) went on to demand honest trading, higher wages, lower rents, relief for the beggars on the streets, and an end to the enclosure of the people’s common land.

In south England an egalitarian message had already been promoted by the Levellers (who demanded equal rights) and by the Diggers (who farmed the common land), so Quakers initially spread from the Midlands to the north. But after both the Levellers and the Diggers had been crushed, the Quakers filled the vacuum. They became well organised and in 1652 moved south from Cumbria into the areas where the Levellers had once been prominent.

On his release from prison, the leading Leveller, John Lilburne, became a Quaker, as did the leading Digger, Gerrard Winstanley. The Marxist historian, Edward Bernstein, explained it like this: the Quakers, Levellers and Diggers were “the extreme left” of the revolution.

Quakers survived where Levellers failed because they had an ethical dimension. While others withdrew from social and political struggles into spiritual self-contemplation, or engaged successfully in society but lacked an ethic to survive the perils of success, Quakers survived largely because they believed social classes and conscience were part of the same thing.

Fox, for example, thought it was class society that was blocking his spiritual development. He believed, “Christ had come to teach his people himself”. And everyone – not just Europeans, not just Christians, not just the upper classes – could find the ‘Light’ within themselves. By sitting in silence, and allowing the inward Light of the egalitarian Christ to shine upon conscience, the truth would emerge, both spiritual and social.

Colleges of industry

John Bellers, a young contemporary of Fox, has often been called the pioneer of Quaker socialism because he put the labouring classes at the heart of his work. He proposed in 1695 “colleges of industry” for the unemployed and poor, arguing that all of a nation’s wealth arises from skilled labour applied to natural resources.

For this theory, and his idea of worker co-operatives, Bellers received high praise from Robert Owen and Karl Marx. He also proposed a united nations assembly to bring about world peace. Each country would be represented according to population, and international problems would be resolved on the pacifist basis that all killing is wrong, a core tenet of Quakerism.

Quaker socialists have other role models besides Fox, Bellers, Lilburne and Winstanley. In Mansfield, Elizabeth Hooton supplied Fox’s basic ideas, derived from Anabaptist sources. Margaret Fell, Fox’s wife, championed the equal rights of women. William Penn made an exemplary treaty with the American Indians and, like Fox, attempted to phase out the slave trade (given that abolition was at that time out of the question).

Quaker socialists also revere the 18th century American, John Woolman. He campaigned to end the slave trade while adopting a lifestyle of utmost simplicity, taking equality to a new ethical standard.

Elizabeth Heyrick is honoured as the ‘first Quaker socialist’. She campaigned, not only for the abolition of slavery, animal rights and prison reform but crucially for industrial workers and the new trade unions. It was in 1827, during Heyrick’s lifetime, that the word ‘socialism’ was used for the first time.

In 1898 Mary O’Brien set up the Socialist Quaker Society (SQS). This comprised a few disillusioned Fabians, such as O’Brien herself, but mostly attracted supporters of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) led by non-Quaker Keir Hardie. These Quaker socialists wanted to win elections and establish a Labour party in parliament but – harking back to Bellers – they were also interested in municipal co-operatives.

Indeed, Hardie defined socialism as “a co-operative of co-operatives”. The ILP’s Ada and Alfred Salter combined both approaches: Alfred got himself elected as an MP, while Ada ran an ILP co-operative, and campaigned locally for clean air, model housing, and beautification of the slums.

Indeed, Hardie defined socialism as “a co-operative of co-operatives”. The ILP’s Ada and Alfred Salter combined both approaches: Alfred got himself elected as an MP, while Ada ran an ILP co-operative, and campaigned locally for clean air, model housing, and beautification of the slums.

During the 20th century many Quaker socialists became prominent in society and the arts. Among them were John MacMurray, the Scottish philosopher; Joseph Southall, a radical artist; Joan Baez, the US folk singer (pictured left); Paul Oestreicher, a peace campaigner; Bayard Rustin, a civil rights organiser; and Philip Noel Baker, winner of the Nobel Prize for Peace.

Liberal resurgence

However, this swing to the left faded in the early 1970s. The number of working-class Quakers dwindled and liberal Quakers, alienated from the left by the militancy of the period, resumed their natural proximity to the establishment. Towards the end of 1975, the Quaker socialist Ben Vincent founded the Quaker Socialist Society (QSS) as a reaction against this liberal resurgence, and this was quite a success.

In 1995, QSS managed to persuade Quakers to agree to a ‘Social Testimony’, and since 1996 it has organised the annual Salter Lecture (in memory of Ada and Alfred Salter), held at the same time as the Quaker Yearly Meeting. This popular lecture (see YouTube) has now been delivered by many well-known academics and MPs, such as Danny Dorling, Diana Jeater, Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn.

In 1995, QSS managed to persuade Quakers to agree to a ‘Social Testimony’, and since 1996 it has organised the annual Salter Lecture (in memory of Ada and Alfred Salter), held at the same time as the Quaker Yearly Meeting. This popular lecture (see YouTube) has now been delivered by many well-known academics and MPs, such as Danny Dorling, Diana Jeater, Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn.

Nonetheless, despite the existence of QSS, the liberal majority within Quakers has shifted Quakerism increasingly towards the establishment. Compromises have resulted from membership of Churches Together (which Vincent warned against), from conservative interpretations of the Charity Act, from commercialisation of services, and from the dilution of internal representative democracy.

The radical history of the Quakers (on slavery, as conscientious objectors, on business integrity) has been impugned so as to make Quakerism more acceptable to other churches (full of guilty consciences on slavery and war), or to accord with the performative ethics of commercial companies.

The aim appears to be to create a modern charity, in which membership and Meeting Houses are surplus to requirements but Quakerism is saved from extinction by drastic surgery.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with modernisation. The majority of British Quakers are now atheists. Liberalism has much to be said for it. Something needs to be done about falling income. But Quaker socialists point out that, in the past, it was the radicalism of Quakers that maintained Quaker identity and membership when the other churches declined.

They offer as an alternative to liberalism the prophetic tradition that came down from Moses, Isaiah and Christ, via the Lollards and Anabaptists, to Fox and the early Quakers, and then to the ethical socialism of the early ILP. This tradition has avoided extinction for more than 3000 years.

—-

Graham Taylor is the author of Ada Salter: Pioneer of Ethical Socialism published by Lawrence & Wishart and available to buy here for £20.00.

Graham Taylor’s ILP pamphlet, Ada Salter and the Origins of Ethical Socialism, can be ordered now from our Publications page.

You can find out more about the Quaker Socialist Society here.

To find out more about Quakers in Britain, click here.

12 May 2025

I’m so glad, Michael, that you found the article helpful. The statistics I used for Quaker belief in God are taken from the Woodbrooke survey as presented to the Future of Quakerism conference in October 2024. The non-believers in God had a slight majority.

However, you are absolutely right to say that “the direct connection to the Divine remains something central to Quakerism”. Those Quakers who say they do not believe in God include many who believe in a universal energy, or a holy spirit, or are Quaker Buddhists. Perhaps the 20% you refer to are the outright atheists.

11 May 2025

Thank you for a very informative article and a reminder of the role of Quakers in the ILP and their broader historical contribution in service of women’s rights, criminal justice reform, peace and the environment. That work continues today. Indeed, there has been something of a revival of interest in Quakerism among young people in our larger cities, notwithstanding the overall ageing profile of members.

I would just like to correct one point. The latest survey for the Future of British Quakerism in late 2023 put atheists at just under 20% of respondents. While Quakers are certainly less Christocentric than in earlier days, the direct connection to the Divine remains something central to Quakerism. Most Quakers in the US, Latin America and Africa – the vast majority of Quakers globally – are still very much rooted in Christian belief.

10 May 2025

An excellent and informative piece. Well done! I hope that the Quaker Socialist Society will keep in touch with the ILP and keep us informed of what you are up to. Both groups share a commitment to the promotion of ethical socialism.