Independent Women

“No cause can be won between dinner and tea, and most of us who were married had to work with one hand tied behind us.”

Hannah Mitchell: The Hard Way Up: the Autobiography of a Suffragette and Rebel

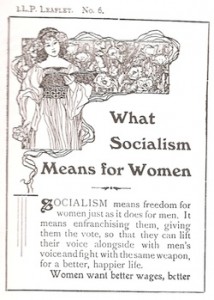

From the beginning, the ILP accepted women and men as equal members and, as early as 1895, it supported the extension of the vote to both women and men.

Although women were not relegated to the background, few were involved at the policy making levels in the early years. However, women took a leading part in branch life and as public speakers.

Many carried out the roles traditionally allocated to women in politics. And some, like Hannah Mitchell found that their husbands were happier talking about sex equality than practising it!

Some ILP women were at the forefront of campaigns to improve the lives of poor, working class children in the cities. In Bradford, Margaret McMillan’s pioneering work for children and for school meals won her fame as an educational reformer.

There was one woman on the party’s first national council, Katherine Bruce Glasier. Others were to follow, including the suffrage campaigner Isabella Ford of Leeds. She had been a supporter of the celebrated strike at Manningham mills, Bradford and played a leading role in encouraging women textile workers into unions. In 1905, she was supporting striking mining families who had been evicted from their homes by their employers in Kinsley, near Hemsworth in Yorkshire.

Explaining why she joined the ILP after she had been impressed by its support for women, Isabella Ford said:

“My last doubts were removed after a visit to a Labour Club in the Colne Valley, where the men had been giving a tea party to the women, and had poured out the tea, cut the bread and butter, and washed everything up, without any feminine help and without any accidents! A party, that included the education of men, which had hitherto been so much neglected, as well as the education of women, that gave the one such skill and dexterity, and the other wider and truer views of life, was the party for me I felt, and so I joined.”

When the Pankhursts’ votes-for-women campaign folded with the outbreak of the First World War to further the war effort, it was largely those women in the ILP and the peace movement who continued their dogged work in the school boards and as poor law guardians.

Many thousands of women were also active in the wartime peace movement, and others continued the work of Enid Stacy and others who campaigned for:

- The right for women to choose whether or not to have children.

- Equality in marriage and fair divorce laws.

- The right for women to have guardianship of children.

- Full legal and political rights for women.

- Freedom as workers, including protective legislation for men as well as women.

The years between the wars were difficult ones for women raised during the heady days of the pre-war suffrage campaign.

Inside the Labour Party, ILP women played a distinctive role. Dorothy Jewson and Dora Russell fought to improve women’s’ status in the party were at the forefront of campaigns for birth control and peace.

In fighting for women’s independence, such women found themselves confronting a cautious labour movement afraid of upsetting the voters. They found that winning votes usually took precedence over winning people’s hearts and minds.

As a result, many women became disillusioned with these short term considerations. Others, like Hannah Mitchell, undertook new responsibilities as local councillors.

Votes for Women

The ILP was closely involved with the campaign for votes for women before the First World War. But the issue was not a simple one. There was a heated debate about how to, given the fact that not all working class men had the right to vote either. Some favoured militant action, others persuasion.

Some campaigners argued that women should have the vote on the same basis as men, whilst others said the vote should be extended to all men and women at the same time (the adult suffragists).

These disputes were reflected within the ILP which had attracted many women because of Keir Hardie’s and others’ commitment to the women’s cause. There were, though, many men in the ILP who still had to be persuaded.

Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst drew many of her women activists from ILP members and the ILP had supported the suffragettes. But the increasingly separatist nature of her Women’s Social and Political Union and its undemocratic leadership led to a rift between it and the ILP in England. In Scotland, however, the two organisations continued the work hand in hand.

The ILP’s concerns were much closer to those of the largely northern, radical suffragists who called for ‘womanhood suffrage’ and believed that “it is from a truly democratic organisation alone that satisfactory results can be expected”.

In these campaigns working class women with little or no education learned to be outstanding public speakers and grass roots organisers, touring Britain in the Clarion vans.

Self-taught women who learned their politics on the job like Selina Cooper from Nelson and Ada Neild Chew from Crewe who were supported by middle-class, women speakers and writers like Enid Stacy. She made one of the earliest attempts to bring together the ideas of feminism and socialism.

In the last thirty years, feminists have been discovering the work of the women pioneers and many have been inspired by their example.

—-

This is an extract from the original centenary edition of The ILP: Past & Present, published in 1993. The print version is now sold out.

The latest revised and updated version, published in 2023 to mark our 130th anniversary, is available to buy in two parts from our publications section.