Unromantic as it may be, without a feasible alternative to capitalism it is capitalism we have to work with, says GARY KENT. At this time, a reformed and civilised capitalism is the best Labour can do, and it is what the public want.

An article on infantile leftism and the future of the Labour Party could start with a smart line from Lenin or Marx but instead I turn to Lennon and McCartney in the 1968 song, ‘Revolution’:

But if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao

You ain’t going to make it with anyone anyhow.

Think Hugo Chavez or Hamas and Hezbollah and you’re bang up to date. Think of the consequences if Jeremy Corbyn were to win.

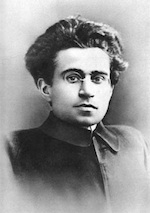

But Gramsci is also apt: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

He was referring to capitalism but I apply it to parts of the left: those who sport t-shirts proclaiming they have never kissed a Tory; who wear images of Stalinists like Che Guevara; who display a smug certainty that the Tories are venal, self-serving and have no justification or rationale for their policies apart from class interest; who dismiss the need to win ‘Tory voters’ as if they are from another planet, rather than people who voted differently on this occasion and are likely to do so again if they are not engaged with. Those who dismiss Liz Kendall as just Tory-lite may satisfy themselves, but they are stuck in an ugly echo chamber.

He was referring to capitalism but I apply it to parts of the left: those who sport t-shirts proclaiming they have never kissed a Tory; who wear images of Stalinists like Che Guevara; who display a smug certainty that the Tories are venal, self-serving and have no justification or rationale for their policies apart from class interest; who dismiss the need to win ‘Tory voters’ as if they are from another planet, rather than people who voted differently on this occasion and are likely to do so again if they are not engaged with. Those who dismiss Liz Kendall as just Tory-lite may satisfy themselves, but they are stuck in an ugly echo chamber.

There’s a rich seam of material to demonstrate that parts of the left are delusional. For me, the constitutional role of the Guardian letters page is to remind us of this.

Jack Halinski-Fitzpatrick, for instance, recently rounded on Polly Toynbee, who had had the temerity to criticise Corbyn, and argued that Labour “lost votes to Ukip, which, as well as whipping up some racist jingoistic sentiments, ran on an anti-establishment platform and won support among the white working class. With over 70% of Ukip voters supporting nationalisation of the railways and energy companies, a clear socialist programme could win back vast swaths of support to Labour.”

But softly accepting one item on a left-wing wish list does not translate into openness to a wider socialist programme.

Every movement has logic-choppers who believe their own propaganda and kid themselves that more radical policies can do the trick. And every now and then, a normally conservative society can be open to offers that have been well-prepared and can capture the popular imagination. Think of childcare, the NHS, the national minimum wage.

Anyone who differs from the delusional left is often deemed to have ulterior motives. As one who has long been on the right of the left – and some sneer I am just half-right on that – I often met people who detected devious intent when, for instance, I opposed the Provisional IRA.

Many of us feel a strong connection with those who proclaimed socialism in tough times. We seek inspiration from past Labour leaders. But that doesn’t mean we import every part of their programme, which suited contemporary conditions but are no longer appropriate.

For instance, we can take heart from how Keir Hardie broke the mould of the then Conservative/Liberal duopoly but we would not now support temperance reform, at least as he conceived it. We can celebrate Tony Blair’s rebuilding of the public realm but we would no longer tolerate the Faustian deal with finance capital and light-touch regulation. We can salute Gordon Brown’s herculean efforts to save the banks and avert another great depression but we should reject his damaging stress on tactics over strategy.

Old mechanisms

Left-wing parties everywhere face major crises as the old mechanisms that sustained their support have disappeared with the collapse of the old Fordist economy and the onset of globalisation. Take a look at Donald Sassoon’s magisterial Century of Socialism to see how, for instance, the German and Swedish left once provided a cradle-to-grave alternative society with youth movements, summer camps and strong unions. Now the German SPD and the Swedish Social Democrats are only in power in coalition or have lost to the right.

And we also need to talk about that word, socialist. I know that we put the term in the party constitution in 1995 although we sensibly added the adjective democratic to the front. But I no longer use the term because it is weighed down by so much bloody baggage and has little descriptive power.

Socialism once meant an entirely new system of production, based on need and planning rather than profit, but Labour Party members were divided on the means and the timescale. Revolutionaries within and outside the party – the two were once indistinguishable in the form of my first political berth, the Revolutionary Socialist League, more often known as the Militant Tendency – scorned reformism. Reformists scorned the anti-democratic and anti-parliamentary perspectives of revolutionaries who, if they were prepared to pack meetings and pass motions that had no base, would have been equally capable of taking short cuts with the public and ending up with coercion.

Socialism once meant an entirely new system of production, based on need and planning rather than profit, but Labour Party members were divided on the means and the timescale. Revolutionaries within and outside the party – the two were once indistinguishable in the form of my first political berth, the Revolutionary Socialist League, more often known as the Militant Tendency – scorned reformism. Reformists scorned the anti-democratic and anti-parliamentary perspectives of revolutionaries who, if they were prepared to pack meetings and pass motions that had no base, would have been equally capable of taking short cuts with the public and ending up with coercion.

What helped and enable both strands to stay together was the old clause four of the party constitution, devised by the Webbs to distinguish Labour from the Communists. The famous statement is ambiguous. It says that the aim of the party is: “To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.”

Some focus on common ownership and others emphasise the caveat of what is possible upon the basis of common ownership. Anyway, we scrapped that and the new party aim is in line with what is often described as ethical socialism, which is that contemporary society can be veined through with our ethical values, regardless of ownership. The party is part of a mission to civilise rather than overthrow capitalism.

Marxists argue that capitalism is inherently unstable, and they have a point. But short of a feasible alternative, let alone the chance of winning support for radical change in a society with long established and broadly small-c conservative values, we are stuck with some form of capitalism. The real question is, ‘what sort?’

I am most attracted by the Blue Labour thesis. I understand this to be saying that there needs to be an historic compromise between labour and capital. In return for accepting capitalist relations of production, capital has to accept Labour as a partner. Having workers on the board, together with strong unions (not the hard-left dominated husks we often see now), means we are all in it together. Conflicts of interest do not evaporate but are managed.

The Rhineland capitalist model, from which the idea of workers on the boards is drawn, offers decentralisation, manufacturing, apprenticeships, valuing vocational work and education, and more, with a hefty dose of Catholic social thought on the value of labour. How we get there is another matter. Blue Labour should not be seen as having a monopoly. What is called Blairism also needs to be mixed with it to emphasise, for instance, the need for public sector reform and ways of making use of private management and provision in the public sector.

That also means losing the incredible notion that the Tory danger is the privatisation of the NHS. Yes, they increased the size of the private sector in the NHS by 20% between 2010 and 2015, but that was from about 5% to 6%. Private residential children’s homes, mostly small businesses, have largely worked well for looked after children. With suitable regulation, there is nothing wrong with private enterprise and profit in health and social care. Where there is, we should expect the state to wield a big stick.

Iraq … and all that

And let’s discuss Iraq, the great four letter word in British politics. I backed Blair in the overthrow of a fascist and genocidal regime. Having visited Iraq 20 times since 2006, I know that most Iraqis also welcomed the demise of the despot. The Kurds, who called for intervention, believe that it was a liberation. Iraqis also know that the occupation was a disaster and failed to tackle the remnants of Saddam’s power base or the descent into ethnic cleansing and civil war. It would always have been difficult but the Americans failed to cope with complexity. I also know that most people here do not agree with me and never will.

Iraq has become a cancer at the heart of British politics. There was an alternative represented by our agreed policy on Iraq, passed by a nine to one margin at Labour conference in 2004, and which I helped draft. It acknowledged that those who honourably supported and those who honourably opposed military action in Iraq have united in support of the emerging civil society in Iraq, including various parties, women’s groups and the new, secular and independent Iraqi Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU) which strongly supported the process endorsed by United Nations Security Council for a federal, democratic, pluralist, and unified Iraq, in which there is full respect for political and human rights.

It is a great shame that united campaigns on this basis petered out, that the hard-left anti-war coalition has dominated debates on intervention, and that Ed Miliband shamefully refused to support punishing President Assad for his use of chemical weapons. I know from my visits to Iraq that political, economic and military intervention is sought by people there who cannot by themselves overcome many decades of division.

Labour is at a crossroads. Just after the last election a Conservative MP kindly cautioned me not to be too downcast as Labour lost in 1992 but secured a landslide in 1997. But the difference is that Labour gained seats in 1992 and made the next heave easier. This time we have fallen far behind. Scotland may be lost for a generation, or possibly forever. Ukip is second in about 50 northern seats, without making much effort. We are way behind in the midlands and in the south where there are fewer Labour MPs than men who have walked on the moon.

The Conservatives have a spring in their step and a steely determination to make structural changes that can undermine our already weak roots in the north by becoming a workers’ party. We may mock this and rightly highlight measures, such as increasing the inheritance tax threshold, that undermine fairness but consolidate the Conservative electoral base. We can also take some comfort in the narrow Tory majority and the expectation that it could be riven by division on Europe, the Union and other issues. But Labour has a massive mountain to climb and the crucial thing is credibility.

Party activists will always be more radical than voters, who get the final say. Understanding the limits of the feasible is not the same as simply seeking office. The reason why the worst Labour government will always be better than the best Conservative government is because we have superior values and that shows in making choices often when there are limited resources.

But parts of the left need to shake off the illusion that they are an enlightened vanguard that can lead workers away from their false consciousness. We need to build a more rooted movement that engages with people’s legitimate concerns about those who take the proverbial – whether, for example, that is people who fiddle welfare, those who provide poor services to the public, or companies that fail to honour their moral contracts with them by providing good customer services.

In the absence of a feasible alternative to civilising capitalism, a radical rupture is neither likely nor desirable. If capitalism is to remain the dominant mode of production, we will have our work cut out seeking to reconcile its cyclical nature and channel its animal spirits. We have to fashion a movement that works with the grain of human nature, makes the market work as well as possible and encourages an ethic of co-operation and compassion.

We best crack on with this. Time and tide waits for no man, or woman, and Labour’s future is not sacrosanct. The process of rebuilding a movement will not finish with the result of the Labour leadership election, whoever wins. It is long term, but we need to start urgently. Britain needs a left that can make a difference for the common good.

—-

Gary Kent has been a Labour Party member since 1976 and has worked in Parliament since 1987. He was a member of the ILP’s National Administrative Council in the 1980s. For the last 10 years he has been involved in cross-party solidarity work on Iraq and Kurdistan. He writes in a personal capacity.

A version of this article was first published on the Open Democracy website.

6 August 2015

The only candidate who appears to have put together a half coherent programme is Corbyn. The rest seem to offer disconnected policy commitments and platitudes.

I don’t agree with sections of Corbyn’s programme because, rather like the electorate at large in Cruddas’s analysis, I’m inclined to be ‘fiscally conservative and economically radical’. But at least he has one and I can’t help but get sucked into the extreme emotion that collective political hope evokes – and Corbyn’s campaign is built around that.

If he wins, I hope he learns how to compromise and evolve. Unfortunately, his previous history suggests he won’t.

Bottom line, if he can’t win over some left-leaning and progressive entrepreneurs and SME owners, he’ll achieve very little. You can’t grow the economy out of budget deficit without investment and you can’t entirely substitute state for private investment. His economic thinking needs to be more strategic.

5 August 2015

Gary, You may have seen that the ILP have been pressing for the Labour Leadership Candidates to issue “Manifestos Of Intent”. This item explains what is being pushed and why – https://www.independentlabour.org.uk/main/2015/07/08/campaigners-call-for-%E2%80%98manifestos-of-intent%E2%80%99/

With ballot papers due to be in the hands of those who are entitled to vote in the Labour leadership contest by 14 August, there are now clear commitments from three of the candidates to do this within the next few days. The fourth candidate is Liz Kendall. I have not come across her saying that she will do this. Although at one time one of her campaign team told me that they would pass a request to do this up the line. Of course, she may be producing something that would qualify and I might have missed this commtiment.

If you have any avenues of influence with Liz or her team, then could you try to get her to come up with what some of us are seeking. Time is now off the essence.

Such Manifestos would not only be helpful when it comes to people making up their minds on how to vote, but they would be helpful in seeking to influence the winner over their future direction of travel.

4 August 2015

Thanks, Matthew. I really liked Gilbert’s article, particularly the description of Blairism and his conclusion: “The issue is whether enough of us can find the energy, the patience, the imagination and the openness to build a movement which can open up a new historical phase. Without one, it will make no difference who the Labour leader or the next Prime Minister is: we will all still be the slaves of the City”.

4 August 2015

The piece assumes that Jeremy Corbyn will win and Gilbert makes a fair point. Other pieces have and will critically examine Corbyn’s positions. But the purpose of the essay was not to land many blows on Corbyn but to look at longer-term prospects for rebuilding the Labour movement on Bluish Labour lines. I think that the anger on Iraq underpins the unwillingness to intervene not just militarily but with military support, diplomacy and other means. The disconnect between how 2003 is seen by many Iraqis, certainly the Kurds, and how it is seen here remains huge.

4 August 2015

“The people I know who have become enthused by Corbyn’s campaign are mostly people with no particular political identity, no historic record of militancy, no sense of themselves as outsiders or rebels. Their enthusiasm is motivated entirely by the fact that Corbyn – as desperately unexciting an individual as he is – is the only politician they can remember offering a coherent account of what has actually happened to Britain in recent years that in any way correlates with their experience or their values. In this debate, I suggest, it is not they whose judgements are being clouded by self-regard and self-interest.”

From Jeremy Gilbert’s ‘What hope for Labour and the left?’ on the Open Democracy website. It’s worth a look.

4 August 2015

I have read this article in several online magazines. I admire Gary for being so upfront in his views. However, I think the article lacks focus and fails to land any blows against Corbyn’s campaign. Although it’s written in plain English and tries to present an alternative economic viewpoint, it may even win Corbyn support.

Its first mistake is to imagine that most people consider Iraq ‘the great four letter word in British politics’. Actually, most people – outside the Westminster village – couldn’t give another four letter word about it these days (though of course they are horrified by Daesh). They are much more concerned about another four letter word, ‘debt’. Whilst only a minority continue to be very angry about Iraq, most people probably agree with those with actual military experience, like Dennis Healey, who say it was a trigger-happy venture by politicians who thought military action could resolve deep-seated political questions.

Invoking Corbyn’s opposition to the war against him only serves to strengthen his position. Having said that, I do have some sympathy for Gary’s views. I think that the ‘Stop the War’ movement’s ‘morality’ was a little one dimensional. Hussein was a fascist dictator with a history of genocide. As a result, I found opposing the invasion almost as painful as supporting it and cannot see why people feel justified in thinking themselves morally superior to those who were in favour. But that sort of complication rarely sways an audience.

Its second mistake is the stab at defining the author’s political beliefs (what Marx would have called his ‘political economy’) in the section entitled ‘Old mechanisms’. The summaries of Blue Labour and Blairism do neither justice. Even some of the more intelligent people in Blairite Progress, like Patrick Diamond, have moved on and now have a telling critique of it (a bit too late, but at least they have one now).

Gary defines it oddly (and not in the way that Blair himself did recently in his infamous ‘heart transplant’ speech) as bringing in private sector management to public services. Despite its oddness, I think this is actually apposite. Blair’s policies lead to mass casualisation of the lower paid parts of the Labour force. I would add that Labour’s failure in its early days to control exchange rates caused the erosion of skilled manual labouring jobs as manufacturing declined because of an export crisis. This undermined Labour’s working class support and hardened attitudes to central and eastern European labour migration. We are living with the political and economic consequences of that mishandling of the economy and lack of joined up thinking about social issues.

Meanwhile, Corbyn keeps making attractive policy statements, some of which are superficial and some of which are actually quite good. Even some of the readers of ultra-right wing Money Week like his policy about ending tuition fees by raising national insurance on those earning over £50k. Frankly, Labour’s mainstream just don’t have a credible response to him.