JONATHAN TIMBERS wants to kickstart the left (and the ILP) into discussing the major challenges facing Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. We all have responsibility to come up with some answers.

Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Labour leader was in one sense revolutionary (even if he is not). If he fails, the Labour Party will either return to neoliberalism or end up on the electoral margins. There is no room for a “let’s see how it goes” attitude, as all the signs from the opinion polls tell us that it is already going very badly indeed.

It is time for the ILP to do what it has done before: to challenge the left so that it can become stronger, if it chooses. At the moment the ILP appears to be silent. Perhaps it is overwhelmed by the sudden and unexpected change in the Labour Party brought on by Corbyn’s election.

It is time for the ILP to do what it has done before: to challenge the left so that it can become stronger, if it chooses. At the moment the ILP appears to be silent. Perhaps it is overwhelmed by the sudden and unexpected change in the Labour Party brought on by Corbyn’s election.

This article is an attempt to kickstart it into discussing the major challenges for Corbyn and is a modest attempt at addressing the crisis of Corbyn’s leadership.

It is worth reminding people of the positions the ILP has taken since it re-entered the Labour Party, with the approval of the NEC, in 1975. This is not for the sake of nostalgia, but because it helps identify some of the questions Corbyn should be considering. My intention is to place Corbyn’s leadership within the narrative that the ILP has developed over the last 40 years.

In the late 1970s, the ILP challenged the left’s opposition to the Labour government’s social contract. It proposed a renewed contract making significant reforms in return for pay restraint. Sadly, the suggestion was ignored and the Labour government went down under a wave of strikes in the ‘winter of discontent’.

In the internal civil war that followed Labour’s historic defeat in 1979 and the rise of Thatcherism, the ILP came up with a series of with principled and well-reasoned positions.

As part of the Bennite Rank and File Mobilising Committee, the ILP proposed one member one vote in a new electoral college for party conference, rejecting the attempts of the left to gerrymander the constitution in its own interests. This was consistent with its principle that socialists had to prefigure in their own political behaviour the sort of society they wanted to see.

In the face of Bennite overconfidence, the ILP developed a sophisticated understanding of the obstacles facing the left and its dilemmas within the Labour Party with the concept of the ‘conservative culture’. The ILP understood that the Labour Party played an important historic role in sustaining that conservative culture. This went against the grain of many on the left who saw the Labour Party in romantic terms.

To complicate matters, the ILP was also sympathetic to the pressures that Labour’s leadership was under and the need for compromise. This level of thoughtfulness often annoyed those parts of the left that wanted to simplify politics to questions of loyalty and betrayal. This included Corbyn, who was active in Labour Briefing, which specialised in denunciation.

Rather than talk about the crisis of capitalism, the ILP referred to the crisis on the left, as many of the economic assumptions about the planned economy came under critical scrutiny. This culminated with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of an era of socialist thinking.

The 1990s were a troubled period for the left. It had seemingly run out of ideas, paving the way for the neoliberal takeover of the Labour Party. Underpinning this ideological collapse were profound social as well as ideological changes. The most significant of these was the end of left-wing working class politics.

The ILP pointed out that terms like working-class and middle-class, while they may have descriptive value in particular social contexts, were no longer helpful categories to understand how capitalism subjugates social groups, nor what political strategies the left should adopt.

It looked to new ways of resisting capitalism for inspiration, such as the Zapatistas in Mexico or the fragmented resistance movement to global capital. It was comfortable with the Blairite mantra about “the many not the few”, but continued to use that formulation for radical ends.

Pessimism of the intellect…

Meanwhile, it pointed out the community of interest that existed between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland, explicitly rejecting the sectarian nationalism of the Troops Out movement. It is no overstatement to suggest that the ILP helped to create the right mindset within the Labour Party for the Good Friday agreement, in contrast to the divisive Troops Out movement.

In the new millennium, the ILP recognised that the socialism of old, based around central planning, was dead and buried. It critically examined other left-wing economic alternatives such as co-operation. It acknowledged that left wing politics no longer came with a prescriptive list of economic solutions.

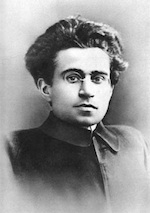

If it had a slogan, and the ILP is averse to slogans, it would have been Gramsci’s phrase about how socialists should face the future – with pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will.

If it had a slogan, and the ILP is averse to slogans, it would have been Gramsci’s phrase about how socialists should face the future – with pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will.

It is precisely this attitude which is required now to salvage Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. Such talk of salvage will be met with incredulity by some parts of the left, still buoyed up on the back of the surge of support that swept Corbyn to power last September.

But the left is running out of time and cannot afford to spend it blaming the predictable resistance of the Blairites in the Parliamentary Labour Party and the old guard outside it. The problems for the left are much deeper than that, as the potted history of the modern ILP shows.

Corbyn’s election as leader of the Labour Party cannot change that history, the fact of the conservative culture, more recent demographic changes, or resolve the crisis of ideas on the left. It merely makes this crisis of ideas more visible to the public.

Corbyn’s election as Labour leader highlights a dilemma for the whole of the left, including the ILP. We had all got so used to pointing out what is wrong, we don’t have a blueprint for how to fix things nor a political strategy to win support to implement it. Indeed, the scary truth is that it may not be possible to work out a complete blueprint. (But don’t despair because George Osborne certainly doesn’t have one).

Shadow chancellor John McDonnell and his friends in the admirable LEAP project have been trying to create a renewed political economy for the left. McDonnell’s much vaunted panel of economic experts is supposed to confer credibility on Labour’s new economics.

But the truth is – despite the recent re-emergence of left wing economic theories – there is a long way to go and now every policy proposal will be subject to the most intense scrutiny. The left has never been able to shake off Mrs Thatcher’s famous saying that “the problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money”. Few people outside the left believe Labour can engender economic growth and end austerity without the support of business (with good reason). McDonnell has to grasp that nettle and soon – no easy task.

Corbyn’s leadership campaign did not do him any favours in the long run. Corbyn badly over-stated the left’s case. For instance, on ending austerity by tackling tax avoidance, Corbyn left out the little matter of the need for a fundamental culture change in HMRC, a raft of international agreements and legislative changes to recoup the lost tax. Clearly, there was no pot of money ready and waiting to be collected and spent.

Then there was the small matter of the £98 billion in corporate welfare, substantial amounts of which turned out to be tax reliefs for research and development and other socially useful activities. And finally, there was the renationalisation of the power companies (total cost perhaps £240bn). McDonnell quickly intervened to save his friend (with an interview in which he talked about renationalisation from below (local authority renewable schemes) and the call was quickly dropped, but Corbyn’s electoral credibility was damaged.

Flip flops and bad jokes

The theoretical and practical dilemmas Corbyn and McDonnell face have resulted in a number of unfortunate flip flops (and a terrible ‘joke’ involving Chairman Mao). Remember McDonnell’s initial support for budget surpluses?

Not all the flip flops have been wise. The pair dropped ‘people’s Quantitative Easing’ (QE), even though this controversial measure could remedy the fundamental problem of too little new money in the economy.

Arguably, the proposal came at a bad time, just as official QE was halting, so the change was understandable. But equally, the fundamental problem that makes people’s QE necessary hasn’t gone away because official QE has been such an abject failure, only serving to make the rich richer and inflate assets.

The Economist expressed this well on one of its recent front covers when it showed an overweight man in a suit looking forlorn and holding an empty bazooka, under the title: ‘The world economy: out of ammo’. Now might be a good time to resurrect the policy.

The flip flop fiascos are not really Corbyn’s or McDonnell’s fault. They have happened because of the left’s lack of a coherent political economy.

Corbyn may recover from his poor start, but it is more likely that he won’t. If he does, it will be because McDonnell provides him with the narrative and the policy substance to do so.

If, on the other hand, he does fail to provide an effective opposition to the Tories, then there needs to be a well-prepared alternative. Otherwise, what may emerge from the electoral wreckage could be some sort of reformist neo-liberal party with or without the name ‘Labour Party’.

That well-prepared alternative should take something from the ILP, old and new:

- The Labour party was never meant to be an evangelical party of the left. That was the old ILP’s role. The Labour party was meant to be a place where people without wealth and status could come together to represent their interests, with a moderate populist agenda. Hardie began it when the ILP failed to make sufficient electoral gains. In other words, Labour began as a compromise, not as a mission. That was a different party, which operated in tandem with Labour until 1932. There needs to be a political strategy that recognises the huge difficulty in asking an electoral party to challenge and change the conservative culture.

- On the other hand, just because the electorate disagrees with the left, it doesn’t make it the mouthpiece for the Sun and the Daily Mail. The left must thrash out a credible narrative about social justice and economic efficiency or people quite rightly won’t vote for it. It has to be seen as a friend of some businesses. Jon Cruddas’s policy review is a start and McDonnell’s panel of economic experts may also help. Not having all the answers might be a positive if it stops Labour from over-promising. The left needs to develop a new social contract with the electorate, offering change, but eschewing magic solutions. McDonnell must show how the state can work closely with business to create equitable growth.

- If that means compromise, then so be it. Reformism is centred around compromise. This may not be a comfortable place for someone on the left, but some tough choices have to be made. It’s more important having the support of the electorate than the organising committee of Momentum or a standing ovation at the LRC conference.

It would be wrong to say that Corbyn’s leadership is futile because his left has neither the ideas nor the support to run a major reformist party successfully. He has catapulted us into a different space where we all have the responsibility to start coming up with answers.

He is in a very difficult position, but if he is clever, he may be able to use it to help renew social democracy. We should support him in this incredibly hard endeavour.

—

See also: ‘The Corbyn Effect’, by Mike Davis, and

‘Is JC Labour’s New Messiah?’, by Jonathan Timbers

30 March 2016

However imperfect Labour’s internal democratic procedures are, in the run up to the last General Election it adopted a promising set of National Policy Forum Reports which shaped its Election Manifesto. The problem is that it did not make any effective use of its programme either with its own members or at the hustings. I summarised its programme (selectively?) in no less than 180 briefly presented points shown for access here –

http://threescoreyearsandten.blogspot.co.uk/2014/11/labours-electoral-programme-part-16.html

Whilst many of the points were (a) generalisations and needed to have harder edges and (b) still had gaps despite their size and scope, there is only a very small handful which I feel that any of us could have had serious reservations about. Would it not, therefore, be helpful for the Labour Party to stress that (until specific items are subject to change via Party Conference) that these points should stand and shape its parliamentary actions? I don’t see any problems in Jeremy Corbyn adopting such a stance. This can be done while still suggesting which areas need to be clarified, what needs to be added and where possible changes can be made (subject to Conference’s agreement).

This approach could be adopted in ways that would make it difficult for right-wing critics of Jeremy to create a groundswell of opposition within the Labour Party and it might help to reign in over-the top tactics from the hard left. Yet it could give us a realistic opportunity for Labour to start out on a programme which gradually and realistically stood a chance of placing what many of the electorate could come to see as acceptable and relevant moves.

28 March 2016

Jonathan’s article started – and Harry has constructively responded to – a crucial debate about the democratic left’s role in a Corbyn-led Labour Party. The political terrain in the party is certainly changing and, I suspect, many of us are struggling with how best to understand and constructively respond to what’s happening.

Of course, the influx of new and returned members is to be welcomed. However, the ultra-left’s re-engagement with Labour on the back of these changes may create challenges for the whole of the party, ourselves included. And the fiercely negative responses from some – but not all – on the Labour right simply spoon-feeds the poisonous Tory press. There is nothing wrong with having lively disagreements. Concern about how the party develops, including its electoral prospects, should be matters for honest and frank debates. But we try to avoid rekindling the kind of bitter disputes that have often bedevilled the party’s history, not least in the Bennite era.

Add to that, the fact that politics in general has loosened from its moorings – what the editor of the journal Prospect calls “the fury against political elites which seems the most enduring legacy of the 2008 financial crash and the Iraq and Afghan wars.”

We have a stagnant capitalism multiplying social inequalities nationally and internationally. We have a European Union which is not fit for purpose and which is feeding insularity, racism and a growing reactionary nationalism. We have social democratic parties struggling for survival as their electoral bases shrink and while they compromise their politics still further. We have the dominance of neoliberal ideas reducing the role of the state, apart from when it’s required to bail out the financiers. This, in turn, feeds a dominant common sense which says ‘Look after Number One and stuff people on welfare’, all of which help sustain the right in politics. And a Conservative government – itself with diminishing electoral support but funded by rich elites – seeking to rig the system permanently in its favour.

And yet, there are signs, particular amongst the young, of counter trends – visible in a variety of movements, often but not always online. A Labour Party which can align with many of these struggles and, dare I say it, which seeks to work with other parties to challenge the Tories, could have a future. The days of ‘ourselves alone’ may well be numbered.

What particularly interests me in terms of the Labour Party itself is the emergence of several new groups. The most well-known is Momentum which certainly has a considerable following and which is trying to establish itself locally as well as nationally. Having recently attended one of its meetings, I found it a friendly and largely positive event. Nor should it be forgotten that some Labour parties and their MPs are responding to the changes positively and this is to be welcomed.

In addition, a new group Open Labour has been established, initiated by Labour councillors but with a wider brief of encouraging a constructive environment for political debate (see ‘A bridge Over Troubled Water’, by Alex Sobel). Even more recently, the group Consensus has been set up, seeking to adopt a positive response to developments. In addition, the long-standing journal, Renewal has two new editors who say they are deeply committed to “honest and open discussion” and who seek to avoid what they see as political “tribalism” inside the party.

They argue that “the current leadership is neither the ultimate cause of the party’s problems, nor (in itself) the solutions to them”, adding “Jeremy Corbyn lacks both critical friends and worthy opponents. Renewal aims to be home for both.” Good for them.

For me, these are all signs that a left could be emerging which is better able to construct a much-needed narrative, one that seeks to connect the party with the wider society; that can help frame a new common sense that helps the Labour Party re-engage with people, to work with social movements and, not least to creatively renew itself. A tall order with no quick fixes but whoever said politics was easy?

I also hope the ILP, drawing upon our rich history, our moral vision and our own attempts to construct a narrative around Unbalanced Britain, will engage with all these and other currents. For me, that also means considering how to tackle the difficult but pressing issue of nuclear weapons and defence. However, that can wait for another occasion…

27 March 2016

Jonathan : Jeremy has moved from the back of the queue within the PLP to the very front with only one jump. To advance his general beliefs he has to move from being a preacher to being its main practitioner in next to no time. He needs some sound advice on how to move the Labour Party in his direction. But he can never ever deliver what he is after in one fell swoop. It is persistent gradualism that is needed, which has to start out from what he inherited. It has to embaces all the major political problems which face us – these are massive. It is a task which all of us need to direct ourselves towards – especially the body which the ILP became when it returned to the fold. It is more than the two of us that needs to see this. We need to keep pushing the ball you have set rolling.

25 March 2016

Harry, your wide ranging response raises a number of interesting questions. I find myself in very much the same space as you: uncomfortable with the current leadership but entirely divorced from the so called moderates.

16 March 2016

Given the situation which Labour faced on General Election day, it is a huge shock that Jeremy Corbyn is now our leader. No-one can have been more surprised about this development than Jeremy himself. He had been Labour’s leading back-bench rebel for years. And although he knew and used parliamentary avenues to push his causes, he was more at home addressing a wide mixture of left-wing rallies – often in the London area and overseas. It was such skills that fitted in so well with his campaign for the leadership. New members were often attracted by what they had picked up about his causes; whilst many established members were looking for a clear break from the danger of Labour returning to a form of Blairism. These attidues packed out his rallies.

I was a member of the Socialist Campaign Group in the Commons alongside Jeremy for 17 years or so. It was contolled by the hard-left – although on occasions they faced shocks. Initially I also joined the soft-left parliamentary Tribune Group. This was to show that ILP-style I was semi-detached from both the hard and soft left. But I withdrew from the Tribune Group as many of its members seemed to me to sell out to Blairism. I remained in the Campaign Group. At times I was with them, but I often took what was normally a minority position. For instance, I followed an ILP style line on Northern Ireland, as mentioned by Jonathan, stressing the need for peace and reconciliation. But when I pushed this line in the Group’s paper (“Campaign Group News”) it was always placed in the “Points of View” section as if I was an outsider. Yet when Gerry Adams wrote for them, it was run as their lead front page article.

Clearly if Jeremy is now to lead the Labour Party effectively, he has to adopt a very different approach to the line he adopted on some key issues in the past. This does not involve him in the selling out his beliefs and values. What he and those around him need to do is to seek to tac and manoevre towards their objectives, taking into account in doing this how they can best achieve a good degree of unity on their approach (a) within the Labour Party and (b) in appealing to the electorate. This entails a constant review of what actions are to be taken. But then when does accomodation to such factors really amount to a sell-out ? We need to square the circle, but with gains and some losses this can be achieved. We need actions which advance our and the electorates’ democratic socialist understandings, but which are not in danger of being counter-productive and setting us further back.

It is what these items are which bodies like the ILP should now be pressing upon the Labour Party and its leadership. For instance, what is the most fruitful approach for us to take over the Housing and Planning Bill which we had such a fruitful meeting on at Leeds? Is there a feasible variant of the view published in an ILP pamphlet in 1980 against Thatcher’s attack on Local Government, which was entitled “The Local Counter Attack”?

There is, at least, one key avenue where Jeremy seems to me to have moved on very quickly following his election. It is of great importance in current circumstances. Traditionally. he was in the anti-EU camp; yet after his election as leader he soon made it clear that he would campaign for the UK to stay in the EU. Since, he has indicated that he supports the progressive line on the EU which has been adopted by the Party of European Socialism. It would be worthwhile now to see this pushed.

As I have argued elsewhere in ILP comment boxes, I thought there were ways in which the above approach could have been adopted on such issues as the vote on the bombing of Syria and the position over the future of Trident. At a more trivial level, it is even possible to appear at Prime Minister’s questions looking smart, without his trousers having to match his jacket.

I am also for keeping a close eye on the work of Momentum and seeking to influence them. I feel that this can be done without signing up to them or becoming a fellow travellor. I receive information from the group in Sheffield and have attended one of their public meetings on local government. They were actually adopting such a moderate stance, that I had to remind them of the Clay Cross Rent Rebellion from 1972 and the ILP’s call for Labour council’s to go into “majority opposition” in 1980. After all, on council housing the ILP has Labour’s first ever legislative success to fall back on – the ILPer John Wheatley’s Housing Act of 1924 which, when Labour then took seats in local government, led to a council house-building boom. My grandmother, uncle and aunt were early beneficaries. Sometimes where we started out from can have a contemporary relevance.