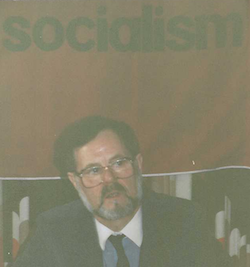

DAVID CONNOLLY celebrates the political thinking of Eric Preston, the ILP activist and theoretician who died a year ago today.

“We live in a world that we could not have predicted in its every detail, but one that does not entirely surprise us. At the ideological heart of socialism is the understanding that the economic imperatives of the unfettered market not only create massive disparities in wealth and power, and exploits resources irrespective of long-term effect, but also undermines the institutions, damages the social framework and corrodes the values and moral authority on which a good society and interdependent social order depends.”

This World of Ours (2009)

ERIC PRESTON, who died a year ago today, epitomised what Antonio Gramsci meant when he insisted that if socialists are to survive in a hostile world they must have both pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the spirit.

Eric had plenty of both and it was the creative tension generated by these contradictory characteristics that produced a political activist and theoretician whose persistent and determined search to find a credible way to a better society never ceased.

Eric had plenty of both and it was the creative tension generated by these contradictory characteristics that produced a political activist and theoretician whose persistent and determined search to find a credible way to a better society never ceased.

He was, in the proper sense of the word, political to his fingertips, a thinker in the best Marxian tradition – open minded, constantly amending his analysis of the prospects for progressive change.

Unlike some on the left, while Eric recognised the system generates periodic resistances, he had no illusions about the scale of the challenge. “The plight of the poor and disadvantaged does not automatically engender a sustained political concern,” he wrote in Labour in Crisis in 1982.

He argued that: “With a deep rooted and well serviced conservatism, the ideas and values veined throughout the working class are likely to reflect the common conservative culture of that society.” Moreover, he thought “the very reasonable concerns of working people can stimulate very unreasonable attitudes”, as, for instance, in some people’s misplaced and dehumanising view of refugees and asylum seekers.

He thought it essential that “democratic socialists intent on creating a new social order start by recognising the problem”, and he was critical of those on the Labour left who “tend to deny working class conservatism, as if to acknowledge it would challenge the very notion of class politics.”

Community of socialists

He saw socialism as the antithesis of that conservatism and therefore “a socialist party has to be nurtured and developed in an alien environment”, taking care “not to make obviously impossible demands merely in order to take up critical positions when those demands are not met.”

He sought to facilitate “a community of socialists” who could “develop credible policies that can get a toe hold” in the wider society, pursuing transitional demands which could prefigure the humanistic, caring society we want to see.

For Eric, there was a parliamentary road to socialism, but it had to be linked to an extra parliamentary movement, and it had to consciously learn the lessons of the ‘socialism’ practised in the Soviet Union. It had to value the democratic process in its own right and avoid excessive concentrations of power, which might lead to the creation of a self-serving bureaucracy. He was always highly conscious of what he called “the political shadow cast by a communist experiment whose collapse confirmed the worst suspicions the British public had of it.”

While respectful of Anthony Crosland, “an egalitarian and a democrat”, Eric was critical of right-wing revisionists in the Labour Party. And he thought the Labour governments of the 1960s and ’70s had, in a variety of ways, “aided and abetted the development of right-wing attitudes and ideas in the wider society” by their uncritical acceptance of an economic orthodoxy which blamed the “greed” and “selfishness” of militant workers for the problems of the day, thereby fostering a de-politicisation of its working-class base.

In Labour in Crisis he wrote, “the working class are never prompted by the right wing to question the way power is distributed or the way society is organised” – a self-reinforcing position and an electoral Catch-22 which continues to this day. “We are damned by the legacy of Labourism and Stalinism” was his verdict in the 1980s.

Thus, in Building Class Based Politics (1991) he argued that: “We now find ourselves in a situation where the accepted definitions of what is happening, the definitions of how society works, and the interrelationship of the parts to the whole, are definitions of the right. The conservative culture is being strengthened at the very time of capitalist crisis, at the very point when it is manifesting some of its worst characteristics.”

Challenging leftism

The best hope for the Labour Party, he thought, was for it to embody some form of “politically honest co-existence” between its various elements, saying “it is ridiculous to pretend that we all are, or have been, moving towards the same destination”. This co-existence should be based on a neutral constitution with democratic outcomes respected by all sides, left or right, regardless of which side wins or loses.

Eric’s belief was that Labour should be a model of participatory democracy at its best. In the 1980s, for example, he argued the case for one member, one vote for parliamentary selections (with a meeting attendance qualification) when every other group on the left saw OMOV as a grievous heresy.

And it was in that spirit of democratic participation that he approached Tony Blair’s move in 1995 to replace the old Clause 4 with a new statement of purpose. Stirring considerable controversy among left-wing colleagues who opposed the change, he saw it as “an ideological pitch” that provided the left with “an opportunity to debate issues of principle, contest definitions of terms and propose policy compatible with what we define to be worthwhile reform”. (An ILP Agenda)

And it was in that spirit of democratic participation that he approached Tony Blair’s move in 1995 to replace the old Clause 4 with a new statement of purpose. Stirring considerable controversy among left-wing colleagues who opposed the change, he saw it as “an ideological pitch” that provided the left with “an opportunity to debate issues of principle, contest definitions of terms and propose policy compatible with what we define to be worthwhile reform”. (An ILP Agenda)

He quoted Hugo Young, who wrote in the Guardian (14 March 1995) that writing new words to Clause 4 “sets a future test for ministers in the Blair government which they might find irksome… Having written them, the leaders ask to be held to them. There will be an awkward reckoning. How many Labour leaders since the war have been seriously asked by the party to prove how far they’ve implemented Clause 4? The new constitution will be a rod for the leader’s back that Wilson never had to bear.”

Challenging orthodox leftism, Eric saw this as “a contemporary reference point”, an opportunity to argue about the definition of terms and how they might be interpreted in policy proposals.

For example, where the Blair statement talked about ensuring that “those undertakings essential to the common good are either owned by the public or accountable to them”, he saw this as “an opportunity to reaffirm that public ownership and/or control should be sought on grounds of social responsibility, extending the principle of universality, efficiency and equity”, and he thought these principles should have a wide applicability.

In essence, his approach was to use an unexpected political situation, one not of our creation, to put the leadership on the spot about when, where and how the principles should be implemented. Unsurprisingly, for those who instinctively saw the new statement as bourgeois reactionary claptrap, his argument cut no ice at all. No doubt he would have proposed a similar argument to the current Labour left about Keir Starmer and his ‘Ten Pledges’.

Economic democracy

Eric also stressed how important it was for the left to say something about what a socialist society might look like and how it would operate, especially as he was acutely aware that all forms of traditionally conceived socialisms – whether social democratic, communist or Trotskyite – were in deep crisis and he knew this crisis was not a passing phase.

He believed “the extension of democracy and the pursuit of the democratic society is at the heart of socialist politics – the core principle of a broad alliance for socialism”.

Moreover, he argued that: “We need to talk more about what kind of society we hope to achieve, no matter how idealistic some Marxists may regard this exercise. We need to know something of the contours of a socialist society. We need to have specific ideas about its economy and how it will work. And we need also to argue why it is necessary to ensure a plurality of power and to say something about the checks and balances needed to prevent excesses like Stalinism.”

The pursuit of greater economic democracy was, therefore, a central idea for Eric and he looked to the work of Peter Abell, Alec Nove and Michael Harrington (one of the founders of Democratic Socialist of America, now an influential force in the Democratic Party) for inspiration about what a decentralised, democratic, socialist economy might look like, including the specific role of market mechanisms in an equitable and egalitarian society.

In short, he wanted to give people a reasonable idea of what a different kind of world might look like and, in this respect, we still have a mountain of work to do.

He was also keenly aware that a future society would have to be environmentally sustainable. In 1991, when climate change seemed to be a very distant prospect to most, Eric warned about “the use and rate of consumption of resources, the amount of pollution and despoilment associated with extraction and manufacture” as a fundamental threat to global sustainability.

In This World of Ours (2009), he wrote: “We need to emphasise the essential nature of an ever-expanding global economic system that, driven hard by the profit motive, must forever encourage a pursuit of wealth and a self-centred consumerism, and thereby drive us beyond the limits of the earth’s resources and towards a major humanitarian and environmental crisis.”

That crisis is now with us, much sooner and far worse than most of us ever imagined, which makes it all the more urgent that we “fashion a clear, coherent, credible and comprehensive alternative”, as he wrote in Labour in Crisis. “We have to encourage a new, radical, socialist, end-orientated vision and an irrepressible new hope for a socialist future. We have, in short, to become a hegemonic force. We have to start the ‘assault on heaven’.”

Eric Preston was indeed Gramsci’s pessimist and optimist all rolled into one. He is sorely missed.

—-

Eric Preston died on 20 September 2020. You can read Eric’s obituary in the Guardian here.

David Connolly’s appreciation of Eric’s life is here: ‘Eric Preston: A Life “Lived for that Better Day”’.

The ILP hopes to compile and publish some of Eric’s selected writings over the coming months.

22 September 2021

Both Eric and I were sons of coal miners, starting our working lives as clerks, undertaking our National Service in the RAF and moving to an anti-Communist stance as a consequence of the Russian invasion of Hungary in 1956. He became a member of the ILP which had defected from the Labour Party back in 1932, but he became a leading figure arguing for it to re-associate itself with the Labour Party.

When this was finally achieved I was lucky enough to come across an initial copy of its newspaper in the main library in Sheffield. The ILP’s paper had initially been called Labour Leader but on its departure from the Labour Party the title was changed to Socialist Leader – the original title was re-adopted when it became a publications organisation.

I was immediately attracted to the line being argued by Eric and others, so I soon joined the reformed body, writing my first article for Labour Leader in October 1975 about the Clay Cross rent rebellion, Clay Cross being part of the constituency area in which I was active.

Alongside Eric I came to serve on the ILP’s national adminstrative council. Although we didn’t always agree (which does not always happen in democratic organisations) I found him to be highly committed, fully active and solidly involved. He was a fine person to have known and to have drawn from. He is greatly missed.