Before he died, Walter Smith wrote a personal account of growing up in a left-wing household at the start of the 20th century. It is, says MATTHEW BROWN, a poignant reflection on the hopes and failures of the socialist movement.

Like numerous working class children born in the early part of the 20th century, Walter Smith was “a child of socialist parents”, brought into the world by two of the many thousands of men and women who committed themselves to an emerging and increasingly confident movement.

Unlike many of his peers, however, Smith’s lived experiences have been saved from the graveyard of history thanks to his own foresight in writing them down and the diligent work of his son, Andrew.

Unlike many of his peers, however, Smith’s lived experiences have been saved from the graveyard of history thanks to his own foresight in writing them down and the diligent work of his son, Andrew.

Smith’s memoir, Born into Socialism, was written in “about 2003”, some eight years before he died aged 96. The text was later edited by Andrew before being published by Gretton Books last year.

It is an admirably brief, admittedly sketchy, but nevertheless poignant reflection of growing up in a left-wing household at a time of enormous social turmoil and rising hope for working class people and the socialist cause.

As such, it joins a handful of other recent self-penned family tales – such as Edith’s Story, reviewed by Harry Barnes – in offering valuable insights into the lives of those otherwise forgotten men and women who did so much to shape the labour movement as an enduring force for change.

Smith’s socialism ran in his Black Country family. His mother’s father, for instance, “had something of a reputation for confronting authority”, and was sacked from one job for starting a union, while his own father was a union activist who lost work after being spotted at a socialist meeting by a police spy. He later became a lecturer for the National Council of Labour Colleges.

Inevitably, it was socialism that brought his parents together. Thomas Smith and Elizabeth Evans met through the Clarion Cycling Club in Dudley, became friends with notable radicals such as Katharine and John Bruce Glasier, and were young activists in the ILP at around the time it was striving to found the Labour Party, hoping to become – in Keir Hardie’s memorable words – “what steam is to machinery, the motive power that keeps all going”.

The couple married and settled in West Bromwich where the author’s older brother, Tom, was born in 1912, followed by Walter in 1917, a year of no little significance for world affairs. As Walter puts it: “I piped into the world as so many screamed out of it in Flanders Fields.

“In that year was launched the left wing’s great hope,” he adds, “the Russian Revolution, whose leaders were to prove more ruthless than any tsar and the great betrayers of a cause.”

Betrayers they may have been, but not in 1917, not to Smith’s parents, at least, who became committed Communists and unshaken believers in the Soviet Union, in his mother’s case even decades later despite all the shocking revelations about its horrors and shortcomings.

Growing doubts

Smith’s reflections on his family’s political journey – from ILP to CP to sceptical resignation – forms much of the second half of his book, including memories of a 1930s visit to Moscow when he spotted Stalin himself sailing by “in a huge limousine”. He noticed, too, how much of their trip was carefully orchestrated and closely “tagged”.

Walter’s growing doubts about the Soviet dream weren’t shared by his parents, however. “It was then I realised my family had embraced the Communist dogma,” he writes, “something I could never quite accept… With hindsight I realise how completely taken in the Communist rank and file were.”

Walter’s growing doubts about the Soviet dream weren’t shared by his parents, however. “It was then I realised my family had embraced the Communist dogma,” he writes, “something I could never quite accept… With hindsight I realise how completely taken in the Communist rank and file were.”

There was, he says, “an essential split in opinions” on the left – the Communist believers on one side, his parents and brother included; the ILP and Labour members on the other.

What comes across through Smith’s sometimes erratic prose is a lasting sadness at his parents’ lifelong sacrifice for a cause that ultimately proved so false. His mother, in particular, he says, “struggled to the end to preserve her faith in Soviet Russia. It was all wishful thinking. Basically, what she wanted was a peaceful, caring world.”

His father, on the other hand, “grew quieter as time passed”.

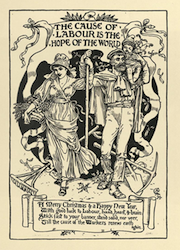

However, Smith does not allow his later disillusion to dampen the warmth of his childhood recollections, including fond memories of Socialist Sunday Schools and a Labour Church adorned with Walter Crane murals, plus a vibrant family home that was “a touch bohemian and opposed … to anything which might appear ‘bourgeois’”.

It was there, crouched on a corner armchair, that he listened to “many interesting conversations” and lively left debates as the house became “a port of call for local comrades”, for whom his father was “a sort of guru”.

Some scenes stand out clearly in his mind, such as the time in 1926 when he looked out with his parents on the “eerie silence” of a deserted high street. “It’s begun”, his father said in “an almost solemn voice”. “It had,” writes Smith. “The General Strike was on. But it had no victory.”

Later, the front room became a bedroom for two tired hunger marchers, “young lads” who’d “had enough when they reached our town”. Other visitors included a glamorous ILP member with film-star looks who died in a cycling accident, while on one family outing he heard Paul Robeson sing ‘Old Man River’.

The book ends rather abruptly after the Smiths’ Soviet trip, with Walter asking, “What of politics today?”

“I think if humanity is to survive (and probably evolve),” he writes, “It will eventually have to embrace some true form of socialism where comradeship does not depend on war, but the interaction of useful, enjoyable activities.”

Over the years, the ILP may have lost its “motive power” to drive the Labour Party, while the Communist promise unravelled across the world. But Walter Smith hung on to the hope of his early socialist upbringing to the end.

—-

Born into Socialism by Walter Smith was published by Gretton Books in 2022 and is available here for £5.00.

See also: ‘A Telling Tale’ by Harry Barnes.