The 1998 Good Friday Agreement that brought peace to Northern Ireland reaches it 25th anniversary on 10 April. The ILP and a grassroots peace movement played an often-forgotten yet important role on the road to reconciliation. GARY KENT aims to put the record straight.

President Joe Biden and a cast of British and Irish politicians will celebrate the 25th anniversary of the landmark Belfast/Good Friday Agreement this Easter. They will rightly hail an accord that ended the Troubles that had cost the lives of 3,600 people, and injured many more physically and psychologically.

But the agreement also owes much to the concerted efforts of many ordinary Irish and British citizens who, over several years, defied the terror groups, some very bravely in Northern Ireland.

But the agreement also owes much to the concerted efforts of many ordinary Irish and British citizens who, over several years, defied the terror groups, some very bravely in Northern Ireland.

Part of the success of the agreement is also due to the work of the ILP whose members helped sustain the peace movement of the 1990s and change the mindset of the Labour Party, leading to major, positive consequences when Labour won its landslide victory in 1997.

The ILP has a long history on the issue. Even back at the start of partition in 1921 the ILP paper, Labour Leader, ran a front-page article that talked of the rock-like reality of the separation. It accepted that partition was due to the gap that had emerged between the two parts of Ireland.

That was not the position of much of the left, which took it for granted that partition was an unfair imposition and underpinned several phases of Irish republican armed struggle in the 20th century.

It’s true that after conceding partition, the British state allowed Northern Ireland to fester as a Protestant-dominated entity that denied basic civil rights to Catholics and working-class Protestants.

Just as civil rights movements in America and elsewhere broke glass ceilings in the 1960s, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), a non-sectarian civil rights movement, began to campaign for equal voting, employment and housing rights.

Protestors were attacked by the armed forces of the then Stormont parliament and pogroms took place in Belfast. Catholics were burnt out of their houses and ethnic cleansing changed the demographic map of the city.

In 1969, the Labour government, driven by Roy Hattersley, sent British troops to Northern Ireland to protect Catholics. It turned into the British Army’s single longest operation.

The NICRA’s demands were conceded in the early 1970s and the Conservative government prorogued the Stormont parliament. By then the fledging Provisional IRA had taken wing and was about to create a miasma of violence that lasted for the next few decades.

Deep concern

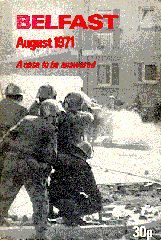

From the 1970s, the ILP concerned itself deeply with the politics of Northern Ireland. It sent a small team to Belfast in 1971 to examine internment and published a pamphlet, Belfast 1971: A Case to be Answered.

It also published a pamphlet by Anders Boserup, a young Danish sociologist who issued a prescient warning to the left not to support sectarian politics.

It also published a pamphlet by Anders Boserup, a young Danish sociologist who issued a prescient warning to the left not to support sectarian politics.

The late Alistair Graham wrote regular articles about the activities of the political wing of the Official IRA, which went through various changes after announcing its formal ceasefire in 1972.

All that work preceded my joining the ILP in 1978. As a callow youth, I denounced the ILP leadership for failing to support the mantras of self-determination for Irish people as a whole and Troops Out Now.

I soon learned better. The ILP’s links with the Workers’ Party (WP) – associated with the Official IRA – opened my eyes to different views, and I was further illuminated when present on another ILP delegation that visited Northern Ireland in 1985.

We sent a delegation to the 1986 Workers’ Party Ard-Fheis conference in Dublin when David Connolly and I interviewed Seamus Lynch, the chair of the Workers’ Party in the north. The ILP also organised a well-attended fringe meeting at Labour Party conference in 1988.

Fellow ILPer Harry Barnes was elected MP for North East Derbyshire in 1987 and I became his researcher. We’d been impressed by the ILP delegation and gradually became more active on Northern Ireland policy. Harry was a guest speaker at a WP conference and in 1990 we helped found a cross-party peace group called New Consensus. We also helped found the British section of the Peace Train Organisation.

These groups were part of a tough-minded Irish/British peace movement which mobilised people for imaginative events that challenged the paramilitary groups and argued they had no mandate for armed struggle.

The Peace Train brought together hundreds of people to ride the tracks between Belfast and Dublin in protest against the Provisional IRA’s bombing and disruption of the line, an odd activity for a movement dedicated to Irish unification.

The Peace Train brought together hundreds of people to ride the tracks between Belfast and Dublin in protest against the Provisional IRA’s bombing and disruption of the line, an odd activity for a movement dedicated to Irish unification.

The Peace Train also visited London in 1991 and highlighted the unity of British and Irish people against terror. The Irish President, Mary Robinson, was its patron. Sinn Fein conferences in Dublin and Dundalk were picketed.

In 1991, another ILP delegation visited Northern Ireland and met all the main parties. I gave an interview to the Irish News in which I took a hard line against the Provisionals, accusing them of peddling conservative views in America while claiming leftist credentials elsewhere. I also argued that knee-capping was an outrage.

The interview appeared on the morning of our meeting in Connolly House with two senior Sinn Fein leaders. Other delegation members joked that we should perhaps not proceed. When we arrived they had the paper open on the table at my interview. Thankfully, we still had a productive discussion.

Reconciliation

In the early 1990s there was a flurry of activities. The ILP established a Socialist Committee on Ireland, of which I was secretary, and sent speakers to Labour meetings. Northern Ireland was regularly covered in the ILP Magazine.

As Labour members, we increasingly focused on the party’s residual anti-partitionism and what seemed to be a solid position in favour of reunification or some form of joint sovereignty.

We argued that unification through violence and duress would not be a wise basis for reconciliation; that the priority should be a largely internal settlement to stabilise Northern Ireland and encourage cross-community initiatives such as integrated education, so allowing class politics to emerge, underlining the common interests of Catholics, Protestants and Dissenters.

We argued that unification through violence and duress would not be a wise basis for reconciliation; that the priority should be a largely internal settlement to stabilise Northern Ireland and encourage cross-community initiatives such as integrated education, so allowing class politics to emerge, underlining the common interests of Catholics, Protestants and Dissenters.

Harry produced regular articles for the newspaper of the Socialist Campaign Group of which he was a member. His was a minority view and a number of others wrote alternative articles, some of which repeated the views of Sinn Fein leaders.

The ILP used various other newspapers to contest the folly of prioritising a united Ireland. I wrote a piece in Tribune in 1994 – during the Labour leadership contest following John Smith’ death – that said: “Labour must now reassess its Northern Ireland policy and listen to the Irish left. It could better promote peace and reconciliation in Ireland if neutrality on the border was combined with a comprehensive peace package that addressed all the causes of the conflict.”

We claimed that Labour’s position was becoming an impediment to persuading unionists that the increasingly likely Labour government would pursue the balanced peace process established by John Major. The romantic desire of many on the left for a united Ireland was built on sand.

Tony Blair was elected Labour leader in 1994 and within months

abandoned the old approach, replacing Kevin McNamara, the veteran

Shadow Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, with Mo Mowlam. He

also gave vital bipartisan support to Major’s peace process and that

helped secure the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement within a year of

Labour’s election.

The ILP had proved that ossified ideas and instincts are a poor basis for policy-making. The peace groups helped delegitimise the paramilitaries’ aims and activities, and our ideas made it easier for Labour to win unionists over to the deal.

Of course, it’s impossible to know what would have happened if the ILP hadn’t made the arguments it thought were right. But it’s at least valid to argue that Labour would not have been able to move so quickly to broker the agreement if we hadn’t been pushing our position.

We were a small group on the Labour left that successfully punched above its weight with fresh thinking linked to a live movement of British and Irish people determined to end the needless terror.

—-

Gary Kent has been a Labour Party member since 1976 and has worked in Parliament since 1987. He was secretary of the Socialist Committee on Ireland and now focusses on Iraqi Kurdistan and Labour foreign policy. He writes a monthly column for Progressive Britain.

He spoke about the work of the Peace Train and other grassroots organisations at a ‘witness seminar’ in Belfast on 30 March organised by the Paving the Path to Peace research project.

On Wednesday 12 April, the ILP is hosting Gary’s talk on ‘The ILP’s impact on the left and the road to peace in Northern Ireland in the 1980s and 1990s’. More details here.

See also Gary’s ‘Building a New Consensus’ and ‘Bordered Minds: A Century of Division in Northern Ireland’, both from 2021.