DAVID HOWELL remembers DH Lawrence and ‘the Eastwood circle’, a dissenting academy in Nottinghamshire ‘with the ILP at its heart’. It is a lost world of Edwardian socialism whose history shows that while vision is essential, it is never enough.

“Keir Hardie stayed with us, Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Edward Carpenter, many others.” Enid Hilton, a daughter of Independent Labour Party parents, thus recalled the Edwardian world of the ILP when branches welcomed propagandists and the occasional party luminary who could inspire the faithful.

Her memory was of Eastwood, a Nottinghamshire mining community in the Erewash valley. Hilton’s father, Willie Hopkin, was the local ILP leader. Once a Nonconformist he had broken with the Eastwood Sunday School Union and instead held open air Sunday meetings to proclaim the socialist gospel.

Eastwood was notable for its Liberalism, not least amongst the miners. The small ILP branch could draw on the language of Nonconformity and claim custody of Radical Liberalism’s unredeemed promises. Its ethical socialism could seem a natural growth from within the community’s respectable culture.

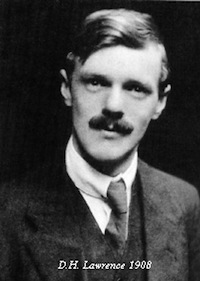

The circle around Hopkin included some who were never members of the ILP, but who were attracted by the debates on cultural and ethical issues held under the aegis of the Eastwood Debating Society. This exemplification of the democratic intellect attracted DH Lawrence during his college years, 1906-8.

Lawrence was responding to a crisis of religious faith by exploring and rejecting scientific materialist alternatives. He found the formalities of college education constraining and arid. This small circle of progressives offered him a space where he could express himself free from the taboos of the Congregational Chapel and the deforming rubric of college. Above all this circle was generous in its enthusiasms – its radicalism embraced political, cultural and sexual issues, a dissenting academy with the ILP at its heart.

Lawrence read a paper to the Debating Society in March 1908, entitled ‘Art and the Individual’. It began: “These Thursday night meetings are for discussing social problems with a view to advancing a more perfect social state and to our fitting ourselves to be perfect citizens-communists-what not.”

His speculations ended with a dichotomy: “In Socialism you have the effort to take what is general in the human character and build a social state to fit it. In art is revealed the individual character.”

This contrast suggests why Lawrence’s prime concern would be rarely political. Yet the Eastwood circle made a significant contribution to his development. He became aware of socialist writers, including Robert Blatchford and Edward Carpenter. He regularly read AR Orage’s New Age, thereby perhaps becoming aware of Nietzsche’s ideas. Alice Dax, wife of an Eastwood chemist was a prominent member of the circle. A committed feminist she would provide some of the inspiration for ‘Clara Dawes’ the working class suffragette in Sons and Lovers.

Lawrence’s early writings demonstrate the influence of his evenings with the circle. The White Peacock presents George Saxton, unfulfilled in his marriage, seeking consolation in alcohol and becoming a socialist propagandist. His sources include both socialist and progressive Liberal writers, people such as Blatchford, Charles Masterman and Chiozza Money. Sons and Lovers in its exploration of feminist claims includes a reference to a meeting addressed by ‘Margaret Bonford’, in reality Margaret Bondfield, an adult suffragist, women’s trade union organiser and ILP member.

In contrast Lawrence’s early dialect plays explore the domestic world of mining families where socialist and kindred influences were minimal. The domestic tensions and miners’ camaraderie that characterised the 1912 strike are presented in short stories and sketches, most notably ‘Strike Pay’ and ‘The Daughter in Law’.

England remade

Hilton’s recollections suggest, perhaps, that the labour unrest that began in 1910 was, in some sense, antithetical to the ethos of the ILP which she fondly remembered. Its high noon was precisely delineated as “strangely alive and rich in that time before the great strikes and the labour troubles, and after the worst of the Victorian era and the Boer War. England was almost remade by groups such as ours in that Midland town”.

This celebration may be excessive but is suggestive. The flourishing of such groups was alongside, and seemingly unscarred by, the controversies that shook the ILP and the wider Labour movement. Hilton’s golden age was the moment of impassioned, sometimes rancorous, debates over ILP strategy, personified for many by the enigmatic Victor Grayson. Perhaps the wellbeing of such local groups was threatened more by industrial conflict and growing trade union strength.

The result could be a loosening of ties with Liberalism and the strengthening of a Labour politics that offered little room for ILP type ethical socialism. This change came slowly to the Nottinghamshire coalfield but perhaps informed Hilton’s epitaph for her golden age: “They were spearheads into the future whose promise has not been fulfilled.”

How far this decline had begun before 1914 is debatable; that the war was decisive is obvious. Lawrence’s response to war was hostile and individualistic. Typically, opponents of the war, whatever their starting points, came together for mutual support. Ethical socialists and radical Liberals co-operated sometimes with lasting consequences.

In contrast, Lawrence’s attempt in 1915 to work with Bertrand Russell ended in acrimony. While opponents of the war and conscription were attacked at their meetings and sometimes gaoled, Lawrence’s war is best captured in the image of his isolation on a Cornish cliff-top writing Women in Love.

His wartime diatribes had many targets, not least on occasions the Labour movement. Yet in September 1918 he speculated that some ILP figures might contribute to the achievement of a radically improved society. He had been aware of Philip Snowden and Margaret Bondfield in his Eastwood days. He also cited Robert Smillie, president of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain and an active ILP member, and Mary MacArthur, a women’s trade union organiser and friend of Margaret Bondfield.

His more typical assessment was deeply pessimistic. Before the war Lawrence had shared a progressive optimism with other members of the Eastwood circle. Now he saw any prospect of decency swept away by the destructive passions of war and the increasingly polarised conflict between capital and labour. His play Touch and Go, written in October 1918, presents Willie Hopkin, thinly disguised as ‘Willie Houghton’. The play begins with a scene reminiscent of an Edwardian Eastwood Sunday morning. ‘Houghton’ speaks to a small crowd of miners, expressing the ethical socialist’s puzzlement and indignation at their apathy and narrowness “If you’ve got plenty to eat and drink, and a bit over to keep the Missis quiet, you’re satisfied.”

His play Touch and Go, written in October 1918, presents Willie Hopkin, thinly disguised as ‘Willie Houghton’. The play begins with a scene reminiscent of an Edwardian Eastwood Sunday morning. ‘Houghton’ speaks to a small crowd of miners, expressing the ethical socialist’s puzzlement and indignation at their apathy and narrowness “If you’ve got plenty to eat and drink, and a bit over to keep the Missis quiet, you’re satisfied.”

Once the miners come out on strike ‘Houghton’ is swept aside as a moralising irrelevance. His socialist vision can find no place in an escalating conflict between labour and capital. “I’m damned, if I’ll take sides with anybody against anything after this. If I’m to die, I’ll die by myself. As for living it seems impossible.”

Such pessimism was unavoidable for those critics of the war who were heavily defeated in the khaki election of December 1918. MacDonald and Snowden headed a casualty list of ILP members and those Liberals who were stigmatised as unpatriotic. Yet the antithesis captured in Touch and Go between socialism and trade union sectionalism, between principle and a destructive irrationality, had been evident before 1914.

MacDonald and Snowden had both attacked pre-war syndicalism on these grounds. Similar sentiments would be expressed throughout the industrial battles of 1919-21 and again during the General Strike and miners’ lockout of 1926. The belief that industrial conflict offered no route to socialism was deeply embedded in the ILP tradition.

Dogged belief

Despite these bruising experiences the pessimism of ILP politicians was always second to a dogged belief in the feasibility of a democratic politics that could advance towards socialism. In contrast, Lawrence’s post-war pessimism was shaped by what he characterised as wartime mob politics inspired by demagogues, most notably Lloyd George. His scepticism about the feasibility of democratic politics belonged within a more thorough exploration of the crisis of wartime Europe, a destruction of that optimism that he had once shared. Dismissal of his post-war writings as authoritarian, proto-fascist and misogynistic arguably mistakes exploration for verdict.

One theme of this exploration clearly connects back to his pre-war experience of ethical socialism, and to the broader cultural traditions of such figures as Thomas Carlyle and John Ruskin on which that socialist tradition drew.

The left internationally was reshaped, first, by the Bolshevik Revolution, and then by the survival of the Soviet Union. Lawrence had indicted the war as the triumph of the mechanical over individuality. He saw Bolshevism as another manifestation of the mechanical with its insistence that Marxism-Leninism was scientific. Lawrence’s Mexican novel The Plumed Serpent portrays Bolsheviks as “the loyal children of materialism”. The novel indicts the frescoes of Diego Rivera as devoid of spontaneity. They were “symbols in the weary script of socialism and anarchism”.

A distinction is sometimes made between moral and mechanical revolutionaries. Lawrence, whatever the complexities of his political responses, stood unequivocally in the moral revolutionary ranks, as did the Edwardian ILP. The Eastwood circle epitomised this politics at a moment of optimism and diversity – a politics of ethical socialism, feminism, syndicalism and radical sexual politics.

Soon, all would be marginalised by social democracy and Third International Communism. Whatever their enmities, for compelling reasons both of these movements prioritised economic objectives. The lost world of Edwardian socialism should be recovered, but its vulnerabilities should be considered. Vision is essential; it is not enough.

—-

David Howell is Professor of Politics at the University of York and author of numerous books on the history of the Labour Party, the left and the ILP, including British Workers and the Independent Labour Party 1888-1906 (Manchester University Press, 1983).

More ILP anniversary profiles can be found here.

16 July 2014

[…] Read his profile of DH Lawrence, ‘Once Upon a Time in the Midlands’, here. […]