With Washington in violent turmoil, Georgia’s historic result provides a model for rebuilding trust in a broken political system. But will Democrats heed the lessons? MARY FITZGERALD and AARON WHITE report from the United States on ‘a radically different way of doing politics, involving long-term, bottom-up organising, led and run by people of and for the communities they serve’.

“People who employ a very shallow analysis of American politics divide us into ‘red states’ and ‘blue states’. But if you peel back the layers just a little bit, you will see that elections have been determined by, one, who shows up and, two, whose votes get counted.”

That’s what Nsé Ufot of the New Georgia Project told us – one of the activists who last week made history by getting out the vote that overturned what she called “the control of conservative Republicans: a pale, male, stale minority that has had an outsized influence on our politics”.

That’s what Nsé Ufot of the New Georgia Project told us – one of the activists who last week made history by getting out the vote that overturned what she called “the control of conservative Republicans: a pale, male, stale minority that has had an outsized influence on our politics”.

Democrats can also partly thank President Trump for their historic Senate win in Georgia. The chaotic scenes at the Capitol Building in Washington DC that followed hard on its heels were a uniquely divisive presidency taken monstrous form.

Trump may have fired up his base – to violent insurrection, even – but he also made himself so unpopular with moderate voters across the country that in Georgia, a traditionally conservative state, they rejected him in their droves on 5 January.

The ‘Trump effect’ was so toxic that Georgians punished Republicans, not only in the November election, when Trump was actually on the ballot, but by an even greater margin last week, when his allies David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler lost their Georgia Senate seats and ceded control of the US Congress to the Democrats.

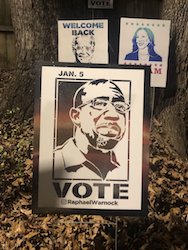

But the result here is about much more than voter disgust – in the words of one Atlanta resident, disgust with the “lying, fear-mongering, science-denying” that the Republican Party under Trump now represents. It’s now well-known that this week’s election of Georgia’s first Black senator, Raphael Warnock, and Jon Ossoff, the first Jewish Senator from any southern state since the 1880s, is the product of many years of focused grassroots organising work.

Years before the Democratic Party establishment took Georgia seriously, a nimble yet powerful operation was being built. Travelling across the ‘peach state’ this month, we got to see it up close. It is the future of political campaigning: inspiring, connected, authentic – and meticulously organised.

Much has been made of the historic voter registration drives run by Stacey Abrams, who narrowly missed becoming Georgia’s first Black governor; by Nsé Ufot’s New Georgia Project; by Mijente, which focuses on Georgia’s fast-growing Latino population; by Helen Butler’s Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda, and many more. Undoubtedly, these efforts played a key role in the Democrats’ victory: more than 800,000 new voters were registered between 2016 and 2020.

But there’s much more to this story. Rights organisations fought and won multiple lawsuits to challenge barriers to voting. Thousands of volunteers drove voters without cars to polling stations. Organisers provided Spanish translation assistance in Latino districts.

Across the state, canvassers knocked on doors, helped people to make voting plans, monitored queues and polling locations, and assisted voters who needed to ‘cure’ their ballots when they were rejected for irregularities. They played music, handed out food and provided other amenities to keep people comfortable while they waited in line.

Climbing the barriers

It is extraordinary how hard it is to vote in the state of Georgia. The services provided by the state are woefully – many say wilfully – inadequate. You need your address, name and ZIP code ‘verified’ just to access basic online information about voting locations. Early voting is arbitrarily restricted, ending five days before polling day.

Some counties don’t open polling stations on weekends, even though they’re legally required to do so. You must provide ID when you vote (a poll tax: many poorer residents don’t have drivers’ licences or a birth certificate). Some polling station locations are changed on voting day without prior announcement, and you’re only allowed to vote at one site. Many stations in heavily Latino areas refuse to provide information in Spanish.

Some counties don’t open polling stations on weekends, even though they’re legally required to do so. You must provide ID when you vote (a poll tax: many poorer residents don’t have drivers’ licences or a birth certificate). Some polling station locations are changed on voting day without prior announcement, and you’re only allowed to vote at one site. Many stations in heavily Latino areas refuse to provide information in Spanish.

Overcoming these barriers has required a massive logistical operation on the ground. But it has also required organisers to connect with people on a different, emotional register: to connect the act of voting with the changes they want to see in their lives and their communities.

It is striking that all four of Georgia’s candidates for Senate pitched themselves as ‘not politicians’. At a rally in McDonaugh, Georgia, on Sunday, the failed Republican candidate Kelly Loeffler told the crowd that she and her GOP colleague David Perdue “aren’t politicians, we’re businesspeople”.

The successful 33-year-old Democrat Jon Ossoff talked up his career as a documentary filmmaker on the campaign trail. And Democrat Raphael Warnock is pastor at Ebeneezer Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King led the congregation until his assassination in 1968.

The symbolism of what Warnock has achieved could not be more powerful. When he was born, both of Georgia’s two Senate seats were occupied by racial segregationists. Georgia’s fast-growing racial diversity – particularly among Latino, Asian American and other immigrant communities – is one of the key reasons this is now a swing state, after decades of Republican dominance.

But the fact that Republicans pitched themselves with racist dog whistles (Kelly Loeffler’s attack ads warned that Warnock would usher in ‘un-American’ chaos) shows just how far this state, and country, still have to go.

“Race has to do with almost everything, unfortunately, in this country, right now,” said Lawrence Miller, a 59-year-old Black former naval officer, voting with his husband in Pittsburgh, a historically Black community in south Atlanta. “There is nothing more important, regardless of what the issues are: and [Republican] legislation is based on keeping one race out and other races down.

“The Republicans under the leadership of Trump … don’t think of us as human. And as a result of that, they feel like they can say anything, any time they want to, any way they want to.”

Yet he also acknowledged that Loeffler made a fatal error when she “pissed off” the Black clergy by attacking Warnock’s sermons. “They’re a dynamic group of people who try to stay as impartial as possible,” he explains. But Loeffler’s attacks made them “stand up and say: ‘Hey, listen, this is wrong. This is just wrong.’”

Watching Loeffler make her pitch to rural White voters from the back of a pickup truck in Henry County, Georgia, the lack of vision and ambition was unmistakeable. With thousands dying from Covid every day and an economic depression not experienced since the 1930s, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Loeffler’s exhortations to “hold the line” and, essentially, keep things the way they are, did not carry her or her party across the line.

It sometimes felt as though Loeffler herself did not entirely believe her own message: once defeated and, in the wake of the violent takeover of Congress the next day, she backtracked on her pledge to join other Republicans in challenging the results of the November election.

The Democrats’ challenge

Looking ahead, the Democrats’ first task is relatively easy. They’re committed to handing out $2,000 stimulus checks to all Americans who earn less than $75,000 a year. Even the committed Republicans we met arriving to vote outside High Falls First Baptist Church in Jackson, Georgia, whose top priority was stopping the “murder of babies”, stand to directly and swiftly benefit from this.

The rest of the task for Democrats, however, will be much harder. As we have seen this week, there is a clear, ongoing threat posed by ‘Make America great again’ diehards, who still refuse to accept the election results (or to take any action to stop the spread of Covid).

The rest of the task for Democrats, however, will be much harder. As we have seen this week, there is a clear, ongoing threat posed by ‘Make America great again’ diehards, who still refuse to accept the election results (or to take any action to stop the spread of Covid).

A far more competent far-right leader than Trump could certainly combine the energy of these diehards with a more broad-based appeal to the many millions, on right and left, still deeply dissatisfied with the status quo. Particularly if, presiding over a fragile political coalition, the Biden administration is unable to take effective action on the economy, jobs and much more.

There are other critical pressures, too. Tomaso is a volunteer canvasser from Oakland, California, who was canvassing on election day in the coastal city of Savannah. For him, climate change is the top issue. While he thinks that Biden’s policy platform is “decent, it’s not enough”, and that even with a Democrat-controlled Senate there will not be the progress needed.

“The problem is, we have a [Democrat] senator from West Virginia [Joe Manchin] who has been in the bed of the coal industry since he was elected. He actually got elected on an advert where he was shooting a gun at the climate bill that was making its way through Congress at the time.

“So with only 50 votes, and that guy representing West Virginia, we’re likely not going get anything through the Senate that will actually improve people’s lives and air quality and stop this inter-generational genocide.”

There is also the question of whether the Democratic establishment will understand and embrace the value of what has just been achieved here in Georgia. It’s a radically different way of doing politics, involving long-term, bottom-up organising, led and run by people of and for the communities they serve.

For Anoa Changa, a Georgia-based journalist who covers electoral justice, both of Georgia’s new Democratic senators, Warnock and Ossoff, “do recognise the value and importance of the movement that was built around them”.

Warnock in particular was an effective candidate, she says, because he did not try to compromise or change who he was. As a pastor, he spoke directly about his faith, and what he and his congregation cherish and value, even when this was viciously attacked. This authenticity was rewarded with the highest number of votes cast in this pivotal election – making history.

And so once again it’s the activists and organisers in this Deep South state, who during the 1960s helped push the US forward with the civil rights movement, that are today sending leaders in Washington a powerful signal about where things need to go next. Will they listen?

—-

Many thanks to openDemocracy where this article was originally published on 7 January 2021.

Mary Fitzgerald is openDemocracy’s Editor in Chief and Aaron White is the North America editor of ourEconomy. Thanks to the authors for permission to use their photographs.

You can read more of openDemocracy’s reports from the US elections here.