It is a common misconception that trade unions founded the Labour Party in 1900. Not so, says JOHN H GRIGG. It was the ILP that drove the initiative.

Just recently I had a disagreement with a comrade who insisted that the Labour Party was founded by the trade unions. My point was that although the trade unions were dominant in the party from the outset they were not the driving force that led to the founding conference in the Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street in 1900.

The meeting was attended by a number of trade unions, the Fabian Society and the Marxist Social Democratic Federation (SDF), plus the organisation I consider to be the driving force, the Independent Labour Party (ILP).

The meeting was attended by a number of trade unions, the Fabian Society and the Marxist Social Democratic Federation (SDF), plus the organisation I consider to be the driving force, the Independent Labour Party (ILP).

During the 1800s, the craft trade unions associated themselves with the Liberal Party, particularly in the mining areas where the Liberals allowed ‘working man’ candidates to represent them. These Lib-Lab MPs were a pressure group within the Liberal Party.

The Fabian Society, one of the socialist societies that attended the conference in 1900, also had links with the Liberals and sought to influence its policies. In the past there had been moves to establish a political party representing the interests of the working classes independent of the Liberal Party. The majority of trade unions did not greet these moves with enthusiasm and they failed to get very far.

One Liberal Party member was Keir Hardie, a coal miner who was appointed secretary of the Ayrshire Miners’ Union in 1886 and successfully persuaded other miners’ unions to join together in the Scottish Miners’ Federation. The Federation sent Hardie to London to try to persuade the Liberal MPs to vote for an eight-hour day for miners. He was not successful and even the Lib-Lab MPs did not back him.

In April 1888 he stood unsuccessfully as an ‘Independent Labour’ candidate at a Mid-Lanarkshire by-election, and a month later he left the Liberal Party and led the foundation of the Scottish Labour Party. His view was that the interests of the working classes could only be progressed by independent parliamentary representation.

Hardie recognised that trade union support was essential if an independent party was going to make progress, but the Scottish trade unions, apart from Hardie’s miners, preferred to stay out of the Scottish Labour Party.

In 1893 Hardie moved beyond Scotland and led the foundation of the ILP at a meeting in Bradford. The name was significant. There had been small groups of trade union candidates and MPs in the past, and one called itself the Labour Party. But they had worked within the Liberal Party.

Hardie’s vision was a party independent of the Liberals, hence the word ‘Independent’. The Scottish Labour Party merged with the ILP a year later and for the first time there was a national organisation seeking to compete electorally with the Liberal Party.

Negligible electoral progress was made and after the 1895 general election, won by the Conservatives, the ILP sought trade union support for independent Labour candidates. At the Trades Union Congress (TUC), resolutions favouring the ILP’s idea were opposed by most old craft unions, but the support of new groups of trade unions representing semi- and unskilled workers, meant enough votes were mustered to get these resolutions passed. However, the resolutions were then referred to the TUC parliamentary committee, which preferred the old arrangements with the Liberal Party, and no action was taken.

A way forward

A way forward emerged at the 1899 TUC when, by a narrow majority, a Railwaymen’s resolution, written by Hardie, was passed to summon a joint conference with ‘socialist societies’ to make plans for parliamentary Labour representation. The resolution’s sponsors persuaded the TUC congress to refer the resolution to a joint meeting of the ILP and the socialist societies rather than leave it in the hands of the parliamentary committee where, it was feared, no action would be taken.

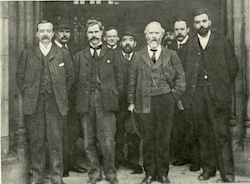

At the Memorial Hall 1900 conference, the ILP was represented by Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald (pictured left with other early LRC leaders) and it was they who drove the project forward. Only a minority of trade unions attended and the powerful miners’ unions continued their arrangements with the Liberal Party. The unions attending represented 353,000 workers compared with the 23,000 combined memberships of the ILP, SDF and Fabian Society.

At the Memorial Hall 1900 conference, the ILP was represented by Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald (pictured left with other early LRC leaders) and it was they who drove the project forward. Only a minority of trade unions attended and the powerful miners’ unions continued their arrangements with the Liberal Party. The unions attending represented 353,000 workers compared with the 23,000 combined memberships of the ILP, SDF and Fabian Society.

Financial support from the unions for the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), as it was initially called, was negligible and was insufficient to employ staff. The unpaid job of secretary attracted little interest and MacDonald, the ILP nominee, was appointed to the post. His appointment was to have a significant effect on the committee’s future.

These early events illustrate the trade unions’ uncertainty compared with the firm commitment of the ILP.

The LRC endorsed 25 candidates at the general election later that year, again won by the Conservatives, but mustered only £32 to support them. They were sponsored directly, mostly by individual trade unions plus a few by the ILP or the SDF. Two were elected: Hardie in Merthyr and Richard Bell in Derby. Bell, however, was soon absorbed back into the Liberal Party.

However, by the end of the 1900 parliament Hardie was not alone and the LRC had increased its number to four through by-election successes. Also, by 1903, affiliated trade union membership rose to well over 800,000 and the only large unions not represented in the LRC were the miners. Money came in from the unions and it was agreed to make allowances to LRC MPs (MPs were unpaid in those days).

What inspired this burst of union interest was the House of Lords Taff Vale Railway decision, which held that trade unions could be sued for damages caused by strikes. The Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants had to hand over £23,000 and the ruling rendered unions powerless. Unions began to see that parliamentary representation was necessary to bring pressure to nullify the House of Lords decision.

At the 1906 election there was a landslide against the Conservatives and the LRC won 29 seats, all but one of them trade union sponsored. From then on the LRC was known as the Labour Party. The Lib-Lab miners’ MPs switched to Labour in 1907, increasing the numbers to 42.

Although Labour had in essence become the trade union party, it would not have existed but for the driving force of the ILP, led by Hardie, which succeeded in spite of reluctance, and even opposition, from much of the trade union movement.

—-

A version of this article first appeared in the Spring 2021 edition of Labour Heritage Bulletin.

John H Grigg is treasurer of Labour Heritage.