The Parti Socialist Unifie ceased to exist more than 30 years ago. But, as one-time member GARY KENT suggests, its grit, principle and foresight has much to teach the modern left on both sides of the Channel.

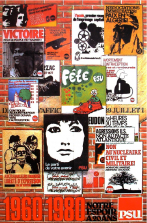

In 1980, a small French party celebrated its 20th anniversary. It was the Parti Socialist Unifie. You have almost certainly never heard of it, but it had a disproportionate and positive influence on the French left before it dissolved itself in 1990.

You may, however, have heard of Michel Rocard, a bright and charismatic founder member who later became prime minister for the larger Parti Socialiste into which many PSUers were absorbed.

You may, however, have heard of Michel Rocard, a bright and charismatic founder member who later became prime minister for the larger Parti Socialiste into which many PSUers were absorbed.

For what it’s worth, I was briefly a PSU member as a student during my year abroad in 1980 thanks to the ILP’s links with the PSU. I was active in the Strasbourg branch and often visited the party’s HQ in Paris. I was briefly, as a courtesy, a member of its International Committee, and I interviewed its presidential candidate, Huguette Bouchardeau in 1981 for the ILP’s Labour Leader.

I also spoke (in less than perfect French) for the ILP at the launch in Paris of its favoured candidate for the 1988 presidential campaign, Pierre Juquin. He was a defector from the Stalinist Parti Communiste Francais with his group, Les Reformateurs.

The PSU was formed in 1960 during a gathering of smaller radical and Catholic groups, and one of its first goals was ending the colonial war in Algeria. Its activities should form part of President Macron’s current attempts to open debate on that filthy war, which caused so many deaths and tainted France. Some of that is portrayed well in the classic film The Battle of Algiers. One infamous incident involved the French police dumping live Algerian activists into the River Seine.

The far right in France was bolstered by the pieds-noirs, French settlers who couldn’t accept the inevitability of Algerian independence. The founder of the Front National, Jean-Marie Le Pen, was himself a French paratrooper in Algeria and proud of his days as a torturer. Another film, The Day of the Jackal, gives dramatic flavour to the story of an attempted assassination of General de Gaulle, who eventually turned on the pieds-noirs.

The PSU was a sometimes eclectic mix. I remember marching under its youth banner, emblazoned with the image of Che Guevara, an odd icon for an anti-Stalinist formation. I used to devour the sober and passionate analyses of its key analysts, Bernard Ravenel and Victor Le Duc. One day, their writings should be retrieved and studied here. All I can say from memory is they were first class.

The PSU was a member of the so-called 2.5 International, its politics located between the decaying tradition of the social democratic Second International (the Socialist Party was originally called the Section Francaise de l’Internationale Ouvriere – SFIO), the discredited tradition of the Communist Third International, and the often ludicrous tradition of the various Fourth Internationals. The ILP was in a similar political place.

Political pioneers

Over the years, the PSU pioneered themes that were later embraced by other left-wing groups after a fight. They championed autogestion – workers’ self-management – which was associated with a battle for workers’ control at the Lip watch factory where a charismatic leader, Charles Piaget, came to the fore. They argued consistently for a 35-hour week and were ahead of the curve in advocating environmental politics.

In 1989, the PSU merged with the New Left for Socialism, Ecology and Self-management (Juquin’s movement), and formed the Red and Green Alternatives (now part of the group Les Alternatifs).

In 1989, the PSU merged with the New Left for Socialism, Ecology and Self-management (Juquin’s movement), and formed the Red and Green Alternatives (now part of the group Les Alternatifs).

The PSU deserves a longer history in English than I can give it now. But during its short existence, it showed what determined and coherent groups can do in making the political weather. To paraphrase Hayek, ideas can make the cut in moments of rupture if they have been honed in fallow times.

In a similar way, the ILP would often do the hard work in thinking things through from first principles, devising feasible alternatives that were scorned and then adopted without so much as an apology for resisting them in the first place, sometimes with great hostility.

For instance, the ILP was almost alone from the late 1970s in advocating one member one vote (OMOV) in the Labour Party on the basis that if you couldn’t persuade party members of radical causes you wouldn’t have much hope with the voters. Previous opponents of OMOV on the hard and soft lefts nowadays take it for granted.

Such is politics. It’s always easier to make headway if you’re not bothered about who gets the credit, although it is frankly galling when you are written out of history.

The modern British left is in limbo: the old analyses are threadbare; the wider movement is a shadow of its former self; too many resist innovation, seeing betrayal at every turn. We should be looking afresh at those whose shoulders we stand on. The PSU was a giant in a small way in the history of the French left whose own renaissance needs some of its grit and principle, as does ours.

—-

Gary Kent has been a Labour Party member since 1976 and has worked in Parliament since 1987. He was secretary of the Socialist Committee on Ireland and now focusses on Iraqi Kurdistan where he is a columnist, a director of a training agency and a visiting professor.