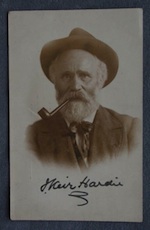

We should remember ‘diverse Keir Hardies’, argues DAVID HOWELL, versions of the ILP founder that stretch beyond the simplicities of socialist canonisation and patronising dismissal, but never attain the dubious establishment honour of ‘national treasure’.

A Scottish Labour candidate campaigning unrewardingly in May 2015 was told by a former Labour voter that if Keir Hardie were alive now he would vote for the Scottish National Party. Alan Johnson, commending Yvette Cooper’s candidacy in the 2015 Labour leadership election, recruited Hardie to her cause as a Labour pragmatist. Gordon Brown’s contemporaneous portrait similarly emphasised Hardie’s tactical awareness but also his authenticity and courage. Biographer Caroline Benn understood Hardie’s life as a continuing attempt to reconcile socialist idealism with strategic constraints.

From a very different vantage point, Arthur Scargill, having quit the Labour Party in 1995, compared his subsequent political home, the Socialist Labour Party’s first under-whelming by-election vote with that of Hardie at Mid-Lanark in 1888.

So many Hardies recruited to legitimise diverse causes. One response is to amend JC Squire’s comment in late 1914:

God heard the embattled nations shout:

‘Gott strafe England’ and ‘God save the King’

God this, God that and God the other thing.

‘Good God’ said God, ‘I’ve got my work cut out.’

A contrasting response by Alan Knight, the historian of Mexico, is to insist that such claims are absurd – if Keir Hardie were around today he would not be Keir Hardie.

This admonition matters because of its insistence on the discipline of context. Understanding Hardie necessitates reconstructing the complexities of his political world, how he understood these complexities and why he made significant political choices. Such understanding necessitates how he might have chosen, but did not, the rich but potentially risky terrain of the counter-factual.

Insistence on context brings us to ‘remembering’; the use of the present participle is significant. No one any longer directly remembers Hardie; instead we construct Hardie and his world from correspondence, including his own and that of opponents, and not uncritical comrades, such as Ramsay MacDonald and Bruce Glasier who both left copious diaries.

Relevant secondary works, not least biographies, must be placed in their own political and intellectual contexts. We each construct our own Hardie, but in doing so Max Weber’s methodological advice is essential: the investigation of any problem, including the initial choice of topic, is shaped by individual biography, not least our values, but such investigation must aspire to objectivity even if inevitably failing in this aspiration. The goal should be an unsentimental understanding of Hardie with difficult questions confronted and ambiguities and silences acknowledged.

Relevant secondary works, not least biographies, must be placed in their own political and intellectual contexts. We each construct our own Hardie, but in doing so Max Weber’s methodological advice is essential: the investigation of any problem, including the initial choice of topic, is shaped by individual biography, not least our values, but such investigation must aspire to objectivity even if inevitably failing in this aspiration. The goal should be an unsentimental understanding of Hardie with difficult questions confronted and ambiguities and silences acknowledged.

The Times obituary in September 1915 serves as a reminder that the vilification and dismissal of Labour leaders with any hint of radicalism, and indeed of anyone whom an established elite saw as a threat, did not begin with Rupert Murdoch. “He was probably the most abused politician of his time, though held in something like veneration by uncompromising Socialists, and no speaker has had more meetings broken up in more continents than he.”

Essentially, for such critics Hardie’s rigidly socialist politics meant he never captured the ear of the working class and was doomed to be the marginalised advocate of unpopular causes.

Three years later a private verdict by Beatrice Webb made similar assertions, albeit more sympathetically. She admitted that her knowledge of Hardie was limited but wished to correct her April 1914 verdict on him as “vain and egotistical”. Rather he had become “the picturesque prophet of the labour movement”. But he was a disheartened prophet.

“To him the regeneration of the world by the upheaval of the manual working class throughout the world had been a religion, and unlike other leaders, notably MacDonald, he had kept himself unpolluted by personal ambition or desire to temporise with the authorities that be.”

This “cultivated man” became disillusioned since “Labour leaders in Parliament were not different from aristocrats and plutocrats in their disinclination to propose revolutionary measures, and were less capable of devising them.” This verdict was underlain by Fabian optimism that wartime collectivism and a burgeoning partnership between sensible intellectuals and the labour movement could solve the dilemma, reconciling Labour’s lack of ambition and socialist idealism.

‘The canonized founder’

Hardie’s authorised biography was published in 1921. The designated biographer had been Glasier but he had died after a long illness in 1920. Instead William Stewart produced an uncritical volume with an introduction by MacDonald. The latter had not been particularly close to Hardie in the immediate pre-war years and Hardie had been dubious about his colleague’s closeness to the Liberals. But in 1921 MacDonald had good reason to write a positive introduction.

The unpopularity of his ambiguous and tortuous position on the war had helped mend his ties with the ILP, as had his 1918 election defeat. His subsequent dismay at what he dismissed as the unimaginative leadership of the post-war Parliamentary Labour Party, the accumulating discontent at the Versailles settlement, the expectation that a Labour government might be feasible, all encouraged him to project himself as the leader an ambitious party needed.

MacDonald could claim to combine principle and effectiveness. He had compelling reasons, then, to write empathetically about the man Beatrice Webb had labelled “the canonized founder” of the Independent Labour Party. To be seen as the inheritor of Hardie’s mantle would hopefully be a source of legitimacy, not least to those on the party’s left.

With MacDonald securely established as leader of the party in November 1922, Labour acquired an invented tradition, an authorised account of how the party had arisen, a usable history that celebrated the party’s British exceptionalism. Within this account Hardie’s place was assured.

His place became even more revered in the legitimising myth that achieved its apogee in the years that followed Labour’s 1945 victory. The celebration of the ‘Forward March of Labour’ appeared credible as the collapse of the second Labour government in August 1931, and the subsequent years in opposition, seemed mere blips in an inexorable advance.

The dominance of such a simplistic history, like that of the Labour Party, proved brief. By the late 1960s the expanding interest in Labour history, the disappointments of the Wilson years, the shift of some trade unions to the left, the growth of Celtic nationalisms, even the crisis in the Six Counties, all suggested the need for a more thorough and sceptical look at the imagery of the Forward March and within that of the politics of Keir Hardie.

So, in 1975, Ken Morgan and Iain Maclean each produced a biography of Hardie. And they were followed soon afterwards by Fred Reid’s study of Hardie’s career to 1895. Within this trio there are differences of interpretation. Reid claims that by 1887/8 Hardie had moved decisively to socialism whereas Morgan’s portrait is more ambiguous, denying any dichotomy and claiming that Hardie was always both radical and socialist.

From these rich contributions Hardie could be located more carefully amidst the rich complexities of Gladstonian Liberalism, ethical socialism and the economic priorities and cultural sentiments of the labour movement. All these currents were contestable; they had affinities and tensions with each other. Moreover, Hardie’s radical Liberal legacy was at odds with the popular Toryism that coloured the socialism of Robert Blatchford and the Clarion.

These studies demonstrated that Hardie, alongside his courage and authenticity, was pragmatic. Such flexibility is evident in the critical choices he made – the Mid-Lanark by-election and the foundation of the Scottish Labour Party in 1888; his entry to the Commons with local radical backing in West Ham in 1892; and his chairing of the foundation conference of the Independent Labour Party the following January are early examples of his tortuous journey through the complexities of the British left. This continued through Hardie’s complex relationship with local Liberals during his 15 years as a Member for Merthyr Boroughs.

His pragmatism was obviously apparent in his critical contribution to the construction of the Labour Representation Committee and, subsequently, to the emergence of a significant parliamentary party. In the mid-1890s he had conspicuously condemned Lib-Lab trade union leaders. William Harvey of the Derbyshire Miners, respectable Nonconformist and regular critic of socialists, was condemned as remote from his members, “in a snug little office with rent and coal paid”.

The even more adversarial and acerbic Fred Maddison was dismissed as “a blustering bully, ill-mannered and with the unscraped tongue of a fish wife”. But Hardie was forced to recognise that his dismissal of officials such as Harvey as remote from their members was simply wrong.

Labour alliance

The October 1897 Barnsley by-election, when the Yorkshire Miners’ Association backed a Liberal coalowner and attacked the ILP candidate Pete Curran, was perhaps decisive. Curran’s heavy defeat led to Hardie and MacDonald promoting the strategy of the Labour alliance, wherein socialists accepted the unions as they were, rather than insisting on their conversion to socialist rectitude.

The relative success of this strategy was facilitated by a succession of anti-union court decisions, most notably Taff Vale. The LRC’s ability to secure union funding could mollify impoverished ILP members concerned about the dilution of socialist principles. Moreover, the union involvement in the LRC impressed Liberals who saw union organisation and cash as valuable electoral resources.

The consequence was the secret 1903 pact with the Liberals permitting LRC straight fights against Conservatives in a small number of seats. The result was a Labour parliamentary bridgehead of 30 seats in the 1906 election, almost all of whom had faced no Liberal opponent. Ironically, had the Liberals in 1903 had any inkling of the massive victory that would ensue three years later, they would probably have regarded such an alliance as superfluous.

The consequence was the secret 1903 pact with the Liberals permitting LRC straight fights against Conservatives in a small number of seats. The result was a Labour parliamentary bridgehead of 30 seats in the 1906 election, almost all of whom had faced no Liberal opponent. Ironically, had the Liberals in 1903 had any inkling of the massive victory that would ensue three years later, they would probably have regarded such an alliance as superfluous.

For Hardie the fact of an independent Labour organisation, whatever the complexities of its relationship with the Liberals, was itself an ideological statement. The LRC, the Labour Party from 1906, was by its existence a statement of working class optimism and creativity, an insistence that working class people were the proper representatives of working class communities.

“The conversion to Socialism and the political organisation of the working class is no light task,” said Hardie in his My Confession of Faith in the Labour Alliance. “The forces arrayed against us are powerful and unscrupulous. We have thus far achieved a very gratifying measure of success, but much still remains to be done. The secret of success has been our ability to unite men of diverse gifts, giving each an outlet for his special talent; by opening the way for the chiefs of the great Labour organisations without loss of self-respect or sacrifice of principle on either side; by magnifying points of agreement and minimising points of difference, and by the exercise of a wise toleration.”

This justification can be cited credibly as an illustration of his pragmatism. Its appearance in 1909 was contemporaneous with the affiliation of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain to the party. The accession of the largest trade union could be presented as the finale to the patient construction of a Labour alliance.

Yet the pamphlet had been written to rebut criticism from within and beyond the ILP, personified for many, in the brief parliamentary sensation that was Victor Grayson. Beyond and partly obscured by these pyrotechnics, were serious concerns about the ILP and its alleged domination by the ‘big four’: Hardie, MacDonald, Phillip Snowden and Glasier. In the eyes of critics they had become a force for conservatism.

A concern about internal democracy connected with two other criticisms, that the socialist voice within the Labour alliance was increasingly stifled by the unions, and that the Labour Party was becoming too close to the Liberal government. Moreover, many of Hardie’s colleagues in the Parliamentary Labour Party could be reasonably described as Liberals with working class accents.

Hardie could be vitriolic in confronting his critics within the ILP, but his pragmatism sat uneasily with his insistence that workers’ grievances must be expressed whatever the consequential offence to the self-consciously respectable and the electorally cautious. His dilemma deepened when the Liberal government introduced the 1909 People’s Budget and came into conflict with the Lords. After 1910 Hardie lived and articulated these tensions with a fidelity shared by very few of his parliamentary colleagues.

These complexities should be located within the context of a historiography first developed in the early 1970s by Peter Clarke suggesting that in Edwardian politics a Progressivism built around a modernising Liberalism and with a stronger Labour component was a more likely future than the disintegration of the Liberals and the emergence by 1922 of Labour as the second party. On this account, to remember Hardie as the forerunner of a forward march that would culminate in MacDonald and, later, Attlee’s arrivals in Downing Street is mistaken.

Changing historiography has enriched understanding of Hardie in ways that go beyond debates about the character of, and prospects for, the Edwardian Labour Party. For example, Caroline Benn’s 1992 biography is notable for its emphasis on Hardie’s family relationships and the consequences of his legacy for future generations of his extended family. This and other work allow Hardie to be located within late Victorian and Edwardian social identities in ways that extend beyond the parameters of Labour politics.

His involvement in spiritualism was not simply an eccentric consequence of his friendship with Frank Smith, much later in 1929, the Member for Nuneaton. Rather, Hardie became involved in a significant movement that connected with the labour churches and diverse ethical bodies. Spiritualism could be understood as democratic practice; within the séance, barriers of gender and class could be transcended.

Similarly, Hardie’s feminism should not be approached through his relationships with the Pankhursts. Women’s suffrage was a vital and divisive issue on the left whether through the debate over women’s or adult suffrage – easily, if misleadingly translatable as pragmatism or purism – or the debate over parliamentary pressure or direct action, whether as alternatives or complements.

Moreover, the suffrage controversy connected with a range of issues around sexual equality and with broader cultural themes. Such issues were often central to the local worlds of the ILP, epitomised by the writings of Edward Carpenter. Sometimes within ILP branches and their associated networks the controversies over parliamentary and electoral tactics seemed far away. Hardie was integral to this ILP culture to a degree shared by few of his parliamentary colleagues.

Ethnic identities shaped many Edwardian political allegiances. Hardie proclaimed his Scottish identity as central to his politics. The Covenanter tradition and Burns provided a radical pedigree. As Member for Merthyr Boroughs he proclaimed the compatibility of nationalism and socialism: Y Ddraig Goch a’r Y Faner Goch; the Red Dragon and the Red Flag.

As an advocate of Home Rule for both Scotland and Wales, his politics, like those of many contemporaries, posed the question of diverse identity within the Union. Remembering Hardie through this diversity illuminates the complexities of pre-1914 political culture and identities. Ireland, not class, posed the major challenge for the British state. Perhaps one counter-factual is legitimate: how would Hardie have responded to the Easter Rising?

Crusader for peace

Beyond the ethnic and religious identities associated with the British state, Hardie is rightly remembered as a crusader against militarism and an apostle for internationalism. In the Anglo-Boer War, despite his robust insistence on Labour independence, he trailed the prospect of an anti-war front that would include that apostle of Liberal individualism, John Morley. But Hardie was also conscious of being a member of a global, English-speaking, white working-class, wherein both class and ethnic components mattered to him. A world tour in 1907 took him to India where his activities provoked the wrath of The Times.

“We have never doubted the power for mischief which persons like Mr Keir Hardie possess, nor their readiness to exert those powers. By selecting Eastern Bengal as the theatre for the display of his qualities as a demagogue, he has given conclusive proof that the estimate we had formed of his criminal ignorance, or his yet more criminal recklessness was all too just.”

Hardie advocated democratisation in India, not British withdrawal; the caricature obscured the complexity of his relationship to empire.

In Australia he met Andrew Fisher whom he had known many years earlier as an Ayrshire miner. In 1910 Fisher would become Australia’s first majority Labour Prime Minister. Hardie welcomed what he saw as Australian egalitarianism, with men from the working class in significant public positions. How far he endorsed the myth of the Workingman’s Paradise is unclear. His response to the Australian Labor Party’s ‘White Australia’ policy was ambivalent. He felt that time would test its feasibility as a means of enhancing living standards, but that the policy exposed the working class to militarist influences. He never considered the policy’s entwining of professed economic interests with racism.

In Australia he met Andrew Fisher whom he had known many years earlier as an Ayrshire miner. In 1910 Fisher would become Australia’s first majority Labour Prime Minister. Hardie welcomed what he saw as Australian egalitarianism, with men from the working class in significant public positions. How far he endorsed the myth of the Workingman’s Paradise is unclear. His response to the Australian Labor Party’s ‘White Australia’ policy was ambivalent. He felt that time would test its feasibility as a means of enhancing living standards, but that the policy exposed the working class to militarist influences. He never considered the policy’s entwining of professed economic interests with racism.

The challenge of race became central when he reached South Africa. Many Afrikaners remembered his support in the recent war, British conservative South Africans attacked him not least for his alleged statements in India. Hardie suggested that white trade unionists, fearing the threat of cheaper black workers, should enrol them in their unions. A strong trade union could say to an employer, “if he was going to employ coloured labour in what was now white men’s work he must pay the white men’s wage, and if he paid that he would prefer the white man all the time.”

Ecumenical unionism on this argument would protect the colour bar by determining employment on ethnic rather than economic grounds. Hardie, after all, could deal in racial stereotypes. He had condemned the importation of indentured Chinese labour into South Africa in the early 1900s and more than 20 years earlier had attacked Irish strike breakers in the west of Scotland coalfields as having small brains and strong backs. He, like many contemporaries, articulated complex relationships between labour ideology, racial identities and hierarchies and the humanism of ethical socialism.

Among all these complexities there is scope for remembering diverse Keir Hardies. These stretch beyond the simplicities of socialist canonisation and patronising dismissal, but never attain the dubious establishment honour of ‘national treasure’.

Whichever Hardie is emphasised, he was never an easy member of any consensus, whether within the left or the wider society. He raised the difficult jarring questions that an established political elite responded to with a mixture of patronage, condescension and outrage. Equally, such insistence disturbed many Labour colleagues keen to emphasise their respectability and willingness to abide by established rules for meagre rewards.

Nowhere was this more evident than when he defended working class people in conflict with their so-called betters. Thus, in the hot summer of 1911 he expressed the anger felt by striking railway workers and their families in their conflict with powerful employers and the state. As a voice for the marginalised he brought an authenticity to debates that contrasted with the apologetic caution of many Labour colleagues. Such authenticity must be at the heart of any remembering of Keir Hardie.

—-

David Howell is Professor of Politics at the University of York and author of numerous books on the history of the Labour Party, the left and the ILP, including British Workers and the Independent Labour Party 1888-1906(Manchester University Press, 1983).

This an adapted version of a talk given at the Working Class Movement Library’s Keir Hardie Centenary Conference on 26 September 2015, exactly 100 years since Hardie’s death.

Read David Howell’s profile of DH Lawrence, ‘Once Upon a Time in the Midlands’, here, and his profile of Clifford Allen, ‘The ILP’s Enigmatic Thinker’, here.

More ILP anniversary profiles can be found here.

More on the ILP’s history is here.