Charles Ammon had a habit of getting sacked for speaking his mind. But he rose from lowly telegraph boy to Labour Chief Whip and the House of Lords. GRAHAM TAYLOR traces the life of a founding ILPer and lifelong socialist who provided support and friendship to the Salters in Southwark.

While researching the life of Ada Salter I repeatedly came across the name of Charles Ammon, a leader of the postal workers’ union, MP for North Camberwell, and a minister in the Attlee government. During my research I had the good fortune to unearth Ammon’s unpublished autobiography in the Hull University archives. It is a lively and fascinating memoir, with moving images of working class life in the late 19th century.

Ammon was born in 1873, in Southwark, not far from Marshalsea Prison. His father was a skilled worker, a cutler and toolmaker, while his mother was “comfortable middle class”. Although they were not poor, there was no welfare state so when his father died in 1884 the 12-year-old Ammon was forced to find employment to support the family.

Ammon was born in 1873, in Southwark, not far from Marshalsea Prison. His father was a skilled worker, a cutler and toolmaker, while his mother was “comfortable middle class”. Although they were not poor, there was no welfare state so when his father died in 1884 the 12-year-old Ammon was forced to find employment to support the family.

His first job was in a bottle factory, earning 15 pence a day, but he was soon sacked, as he was from his next three jobs, all in shops. Finally, at 14, his life was saved by the Post Office. He was employed as a telegraph boy and advanced by studying for civil service exams. He passed them easily, and in 1892 moved up the ladder to become an esteemed post office sorter.

Ammon’s wife, Ada May, later attributed his frequent sackings to his habit of speaking his mind, and urged him to hold his tongue. Fortunately, post office sorters had a trade union and he soon became a union rep, gaining a licence to speak his mind, and the security that enabled him to work for the Post Office for 29 years.

In the end, however, he was sacked by the Post Office too. Civil servants were not allowed to talk publicly about politics and he did. Later, after Clement Attlee made him Chief Whip, Ammon told the press the government’s policy was “crazy” and was sacked for a sixth time.

The postal sorters’ union Ammon joined was the Fawcett Association, named after Henry Fawcett, a blind professor of economics at Cambridge University who Gladstone appointed Postmaster General because of his enlightened views. Fawcett’s wife, Millicent, became leader of the suffragist movement and now has a statue in Parliament Square. Henry gave the post office workers the right to form a union so they named their body in his honour. No other trade union has ever named itself after an employer.

Ammon’s rise in the union movement was meteoric, partly due to his natural ability, which included a phenomenal memory, and partly due to his interest in socialist politics. In 1893 he became a founding member of Keir Hardie’s Independent Labour Party (the ILP) and was soon championing the cause of the workers.

Their main grievance was poor working conditions. Many postal buildings were slums, replete with damp and vermin, and many sorters contracted tuberculosis from working at night in damp, unheated offices. In addition, postal workers’ pay was very low. Ammon used to tell a joke: “Why are pillar boxes red? Because they blush with shame at the postman’s pay.”

Marriage & Methodism

In the late 1890s, the ILP went into decline and Ammon’s political interest subsided. He decided to become a Methodist minister by studying at Morley College. It was tough. When evening classes ended at 10pm, he had to walk three miles home, get some sleep, and get up at 2.30am to be at the sorting office by 4am. He arrived at work with his head full of theology and classical Greek. Ammon notes, sardonically: “I think early rising [is] a greatly over-praised virtue.”

In 1898 the lad from the claustrophobic sorting office married an open-air girl, Ada May, whose father kept a large number of horses in his Walworth stables. It seemed Ammon might be heading for dull respectability, as a clergyman with a well-off wife, but there was always a reckless element to his nature. In this case, before the wedding, he visited Paris with a friend and they stayed until he had spent all his money.

In 1898 the lad from the claustrophobic sorting office married an open-air girl, Ada May, whose father kept a large number of horses in his Walworth stables. It seemed Ammon might be heading for dull respectability, as a clergyman with a well-off wife, but there was always a reckless element to his nature. In this case, before the wedding, he visited Paris with a friend and they stayed until he had spent all his money.

In 1901, he fully qualified as a Methodist lay preacher and, after the birth of their first child, the couple moved to Alscott Road in Bermondsey. There, he played cricket in Southwark Park, and he and Ada taught at a Sunday school in Dockhead.

At the weekend he did some fiery preaching on street corners in the Old Kent Road where his hot cocktail of Methodism and socialism went down very well. The crowds were delighted to hear that God was fully behind the ILP, and fully supported the trade union movement. He was soon a famous street orator, referred to in Bermondsey as ‘Charlie of the Old Kent Road’.

It was not long, however, before the period of marriage, babies, cricket and preaching came to an end. By 1904 the union movement and the ILP had begun to revive. Ammon became editor of The Post, journal of the Fawcett Association, and was regularly writing in the trade union press and attending Labour Party conferences. He put domesticity aside and dedicated himself to a political career.

Although they both lived in Bermondsey, Ammon did not come across Alfred Salter for years because, he says, he was socialist and Alfred was not. The Salters were then in the Liberal Party, although increasingly disillusioned.

The final straw for Ada Salter came in 1906 when the Liberals failed to keep their promise to grant votes to women, despite winning a landslide victory in the general election. Ada immediately joined the ILP, although it was not so simple for Alfred, as he was still a Liberal councillor on the London County Council and lined up to become the next Liberal MP.

In 1908, after consultation with a hesitant Ammon, Alfred broke with the Liberals and formed a Bermondsey branch of the ILP. Ammon was its first chair and Alfred secretary.

The work of the Salters in the 1920s – on health, housing and the green environment – was recognised all over Europe. Over the next two decades, Ammon writes, every major figure in British socialism – Hardie, Attlee, Ramsay MacDonald, George Lansbury – was obliged to visit Bermondsey. “Bermondsey became the centre and inspiration in London and far beyond for socialism,” he writes.

Happy collaboration

In 1909 Alfred stood to become a Labour MP but was defeated because, according to Ammon, he had no trade union support. This did not apply to Ada, however. On Ammon’s logic, Ada’s bid that year to be elected as a local councillor was credible because she had long been trying to unionise women in the local jam and biscuit factories.

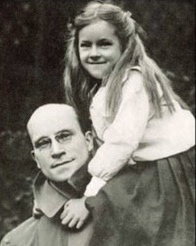

Ammon’s two daughters helped Ada with her election campaign, joining Ada’s daughter, Joyce (pictured left, with Alfred), at a fund-raising bazaar where they ran a hoopla event, a palmistry stall, and charged money for visitors to stand on one of the new-fangled weighing machines.

Ammon’s two daughters helped Ada with her election campaign, joining Ada’s daughter, Joyce (pictured left, with Alfred), at a fund-raising bazaar where they ran a hoopla event, a palmistry stall, and charged money for visitors to stand on one of the new-fangled weighing machines.

Ada won the election and made history by becoming the first woman councillor in Bermondsey and one of the first in England. As Ammon points out, although Alfred started Bermondsey ILP, it was Ada who made the vital electoral breakthrough that opened the door for him and Alfred to be elected as MPs.

Alas, this happy collaboration was laced with tragedy, for Ammon’s only son died in June 1909 and, exactly a year later, Ada’s Joyce died during one of the scarlet fever epidemics that regularly swept through the slums.

In 1911 Ammon became national chairman of the Fawcett Association. In the great strikes of 1911/12 he helped the gas workers, while Alfred aided the railway workers and Ada supported 12,000 women who came out on strike in the famous Bermondsey Uprising.

The Salters now had plenty of union experience but any election ambitions were put on hold when war broke out in 1914. Charles, Ada and Alfred all supported the ILP’s opposition to the war and joined the No Conscription Fellowship (NCF). This took courage at a time when there was a frenzy of hatred, whipped up by the press, against any opponent of the war, whether pacifist or socialist.

Critics of the war were branded as traitors, cowards and pro-German. Both Ada and Alfred had to flee for their lives from buildings set alight by mobs describing themselves as “true Englishmen” and “true patriots”. A mob descended on the Salters’ home in Bermondsey and Ammon lost his job.

The post office sorters were non-political civil servants and in 1916 Ammon was sacked after making a speech deemed to be political. It was a big blow financially since he forfeited his pension rights. He did not dare tell his wife for once again he had lost his job for speaking out of turn, and this time his pension too. Instead, every morning he left the house as normal, pretending he was going to work.

One day, in total despair, he saw Alfred walking down the road towards him, accompanied by the ILP journalist, Fenner Brockway, and the philosopher, Bertrand Russell, leaders of the NCF. He poured out to them his woeful plight and they invented a job for him, making him the ‘NCF Adviser for Trade Union Conscientious Objectors’. He could now go home with a happy smile, and he was soon promoted, becoming the NCF’s lobbyist in Parliament for the rest of the war.

Turning point

The years 1920/22 were a turning point for Ammon, as for Ada and Alfred. In 1920 he became secretary of the Union of Post Office Workers, after a merger with other postal unions. In February 1922 he was elected MP for North Camberwell in a by-election, and in November the ILP won Bermondsey, Ada becoming mayor and Alfred MP. Ada was the first woman mayor in London and the second woman mayor in the whole country.

In Parliament, Ammon’s rise was as rapid as it had been through the union. He was immediately made Labour Whip in the House of Commons and by 1924 was a minister in Britain’s first Labour government, appointed by MacDonald as Secretary to the Admiralty, a job he did again in the second Labour government of 1929.

It was an odd role for an opponent of war and around this time Ammon’s politics seems to flounder. He claims that after 1924 the idealistic ILP of Hardie was finished and only the Labour Party, based on the unions, remained. He writes wistfully that the old ILP had “much the same appeal” as a religious movement, attracting through its humanitarianism men and women unmoved by the more materialistic arguments of the Social Democratic Federation, the Fabians and the Labour Party itself.

The problem, he explains, was that Labour MPs once elected soon became immersed in their parliamentary duties and their principles were set aside. He concludes that when the ILP collapsed in the 1920s Labour lost its “idealistic side”. The Labour Party kept its electoral machinery, but lost its soul.

Ammon’s own idealism seemed unaffected at first. In 1926 he joined Ada and Alfred in supporting the general strike, called by the TUC to help the miners, whose wages were being cut. And in 1931 he and the Salters condemned MacDonald for implementing cuts in unemployment benefits after forming a coalition with the Conservatives. Ammon writes that MacDonald should have resigned and let the Conservative leader, Stanley Baldwin, implement the cuts.

In the 1930s, Ammon had great success on the LCC where he worked alongside Ada, who was in charge of London’s parks, and Eveline Lowe, chair of education. Eveline was Ada’s best friend and in 1940 she became the first woman chair of the LCC, followed in 1941, by Ammon.

What a change over 50 years. From being a telegraph boy in 1892, Ammon was now in charge of London, the centre of the British Empire and still accounted the greatest city in the world.

First Lord

In 1944 Attlee persuaded Ammon to accept a peerage and, as Lord Ammon of Camberwell, he became the first trade unionist in history to be made a Lord.

It all ended in tears in 1949, when Ammon was chair of the National Dock Labour Board. When a dock strike broke out, he called on Attlee to take a tough line against striking dockers who, he thought, were being deceived by Communist agitators. Attlee refused and Ammon called Attlee’s policy “crazy”. Attlee sacked him as Chief Whip, his forthright speech having once again cost him his job.

It all ended in tears in 1949, when Ammon was chair of the National Dock Labour Board. When a dock strike broke out, he called on Attlee to take a tough line against striking dockers who, he thought, were being deceived by Communist agitators. Attlee refused and Ammon called Attlee’s policy “crazy”. Attlee sacked him as Chief Whip, his forthright speech having once again cost him his job.

Before the ignominious end of his own career Ammon suffered the death of his two old friends, Ada and Alfred Salter. In his memoir, he stands in awe of them both. He writes: “Dr and Mrs Salter were the inspirers of revolution, bringing beauty for dirt and sordid ugliness. Under Mrs Salter’s influence … a Beautification Committee was set up… Within two years 9,000 trees were planted in the streets of Bermondsey, against considerable opposition…”

After Ada died in 1942, Ammon wrote: “I have known her for 40 years and still say no one will [ever] know how much she did or how she managed to do it.”

Nonetheless, Ammon thought Alfred the more significant figure. It was he who insisted on founding an ILP branch in Bermondsey and so started the whole ‘Bermondsey revolution’, he says. It was Alfred, too, whose leadership inspired the Bermondsey reforms, and it was Alfred whose medical vision in the 1920s prefigured the National Health Service later introduced by Attlee’s government.

He quotes Brockway’s verdict on Alfred: “I regard the work he did in Bermondsey as among the greatest contributions to social progress in this country.”

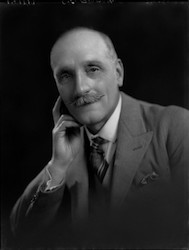

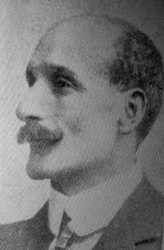

What of Ammon’s own career? He was the great hero of the postal workers, for improving their working conditions, and a champion of slum clearance and education in south London. It is for that reputation, and for being a minister, that his portrait hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

Yet in his unpublished autobiography we see the full humanity that was ‘Charlie of the Old Kent Road’. There, we discover that the honour Charlie cherished most was not being a minister or a Lord, but being granted membership of Surrey County Cricket Club in 1920. For him, that was the sweetest accolade of all.

—-

This article was originally delivered as a lecture on 26 February 2022 as part of the Salter Centenary Project celebrations being held in Southwark, south London, throughout the year.

Graham Taylor is the author of Ada Salter: Pioneer of Ethical Socialism published by Lawrence & Wishart and available to buy here for £20.00.

Barry Winter’s review of the book is here.

Graham Taylor’s ILP pamphlet, Ada Salter and the Origins of Ethical Socialism, can be ordered now from our Publications page.

Click here to read more ILP profiles.