IAN BULLOCK reviews an unusual and valuable account of the ILP before, during and immediately after the Second World War, a period when it hovered on the brink of virtual extinction.

In the acknowledgements to his 2020 book Waiting for the Workers: A History of the Independent Labour Party 1938-1950, author Peter Thwaites states that the book is based on his PhD thesis of 1976, and that his greatest regret in not publishing it for 40 years “is that those ILPers who helped me with information and hospitality are not all alive to see it”.

One of the best and most important features of the book is that it benefits from more than 20 interviews, all conducted between 1974 and 1976. The author also drew on a number of letters from ILPers active during the 1938-50 period. Some of the interviews, but by no means all, are with very well known ILPers such as Fenner Brockway, Bob Edwards and Don Bateman. This gives the book, and of course the thesis on which it’s largely based, a unique quality.

One of the best and most important features of the book is that it benefits from more than 20 interviews, all conducted between 1974 and 1976. The author also drew on a number of letters from ILPers active during the 1938-50 period. Some of the interviews, but by no means all, are with very well known ILPers such as Fenner Brockway, Bob Edwards and Don Bateman. This gives the book, and of course the thesis on which it’s largely based, a unique quality.

But the book doesn’t ignore more recent contributions to the history of the ILP. There are numerous references and citations from much more recent works, such as Barry Winter’s accounts of ILP history, Gidon Cohen’s The Failure of A Dream and or my own Under Siege from 2017. This is particularly true of the first chapter of the Introduction which summarises the history of the ILP from its foundation in 1893 to 1938.

The book’s subtitle might give the idea that it is concerned solely with the years from 1938 to 1950. But the first section of seven chapters also covers the ILP’s organisation and membership, the party’s propaganda work, and its policies, including industrial and international policies, and activities. There is also an appendix covering ‘The ILP and Local Government’.

The second section of a dozen chapters traces the story of the ILP in the immediate pre-war, wartime and post-war years, while an epilogue brings the story more or less up to date with the founding of Independent Labour Publications.

The opening sentence of the Conclusion is unequivocal: “With hindsight it is clear that when the Independent Labour Party hesitated on the brink and then took a step back from reaffiliation to the Labour Party in 1939 it unwittingly doomed itself to virtual extinction.”

The long haul

Yet Thwaites does not think all the efforts of so many individuals were totally in vain. Indeed, it is difficult to believe that the ILP’s determined opposition to nuclear weapons did not, to some extent, prepare the way for CND a decade later; nor that, although unilateral disarmament has not yet carried the day, these campaigns have had no salutary effect on sensitising both governments and public to the dangers, and compelled a more positive, though inadequate, approach to multinational moves towards disarmament.

What’s more, despite the current government’s insistence that it has ‘got Brexit done’ it is at least as possible the same may be true of the ILP’s campaign for a ‘United Socialist States of Europe’. Things always take considerable longer than we like.

Surprisingly, perhaps, in the pre-war years the Labour Party seemed very willing to welcome back the ILP – which would no doubt have been a thorn in the side of the Labour establishment – on the same terms of affiliation it had at Labour’s inception. But after 1944 Labour declared it was “now a unified party which no longer had room within it for a separate party with its own organisation and policies”. This was Labour’s response when the following year the ILP made enquiries about reaffiliating.

Thwaites speculates that this decision was at least partially motivated by concerns that the Communist Party, which had a long history of applying to affiliate to Labour, would pose much more of a threat as it bathed, post-war, in the “reflected glory of the Red Army”. As evidence, he cites Ellen Wilkinson and Harold Laski, who commented on a Common Wealth application to affiliate leading members to Labour’s NEC, saying that any such opportunity would open the way for the CPGB – which seems more than likely.

Difficult stance

The ILP had denounced Britain’s war with Germany as ‘an imperialist war’, a stance it had problems defending given that ILP volunteers, including George Orwell, had gone to Spain to fight Franco’s fascism by force. Claiming the much greater threat of Hitler – to Britain and the rest of Europe – should be met only with the demand for a ‘negotiated peace’ was difficult to sustain, although the ILP always insisted any such position should not be based on an offer the German dictator would conceivably make.

The ILP’s stance seems to have faded after the ‘phoney war’, and, for some, its inadequate response was underlined when its own headquarters was destroyed in the Blitz in May 1941. Indeed, the ILP was ‘waiting for the workers’ not only in Britain but internationally. Not many had responded to its demands for ‘Socialist Britain Now!’

The ILP’s stance seems to have faded after the ‘phoney war’, and, for some, its inadequate response was underlined when its own headquarters was destroyed in the Blitz in May 1941. Indeed, the ILP was ‘waiting for the workers’ not only in Britain but internationally. Not many had responded to its demands for ‘Socialist Britain Now!’

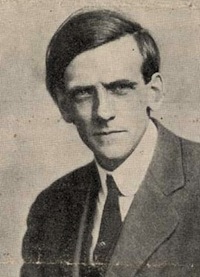

Yet ILP candidates often polled surprisingly well in some by-elections, benefitting from the truce between the coalition parties, and wartime regulations do not seem to have constrained ILP activities very much. Among many other things, we learn from Thwaites that although the Speaker of the Commons refused to recognise ILP MP James Maxton (left) as ‘Leader of the Opposition’ during this period, “he did recognise the ILP as a separate party” with all the appropriate facilities for a parliamentary group.

This, together with the prominence of Maxton and the importance of the ILP’s Glasgow seats, emphasises once again that parliamentary representation remains crucial to most people’s political perceptions and ensures parties get some degree of recognition. On the other hand, Maxton’s role also underlines the dangers to organisations of giving individual figures – however worthy – a cult status.

The structure of this book is unusual, but that does not mean it is not a valuable contribution to the history of the ILP. One can only echo the author’s regret that more of those members interviewed in the 1970s have not survived. It would be fascinating to hear their reflections on the last half century.

—-

Waiting for the Workers: A History of the ILP 1938-1950 by Peter Thwaites (2020) is available here for £19.95.

Ian Bullock is a historian of the early socialist movement and Friend of the ILP.

He edited Sylvia Pankhurst: From Artist to Anti-Fascist (1992) with Richard Pankhurst and wrote Democratic Ideas and the British Labour Movement, 1880-1914 (1996) with Logie Barrow.

He is author of Romancing the Revolution: The Myth of Soviet Democracy and the British Left (2011), Under Siege: The Independent Labour Party in Interwar Britain (2018), and The Drums of Armageddon (2021). His brief history of the Clarion Cycling Club is here.

Ian’s own website on socialism and democracy is here.